English is a quirky language, full of odd rules and expressions that can be downright confusing. Idioms, phrases that can’t be understood literally, are some of the most bewildering. Where do these strange sayings come from? Often, the context we need to understand them has been lost over time. But when we uncover the original stories behind these phrases, they often make a lot more sense. Let’s dive into the surprising backstories of ten popular idioms.

Take a Rain Check

This idiom dates back to the late nineteenth century. Believe it or not, it comes from 1870s baseball. If a game was rained out, teams would reissue tickets for the rescheduled game. These tickets were known as rain checks. By the 1890s, the phrase began to be used more broadly, eventually becoming the way we use “take a rain check” today in situations that have nothing to do with baseball.

Pardon My French

“Pardon my French” is a common phrase, even though it seems a bit strange. It’s usually said after someone swears. But why apologize for speaking French when the offensive word was in English? In the 1800s, educated people often sprinkled French phrases into their speech. Those less educated wouldn’t understand, hence the need to apologize for using French. Over time, the phrase shifted from apologizing for actual French to excusing bad language.

Saved by the Bell

There are a couple of stories about the origin of “saved by the bell.” One popular theory traces back to the 18th century, when people feared being buried alive. A system was created where a string was attached to the finger of the supposedly dead person, connected to a bell outside the coffin. A guard would listen for the bell, just in case the person was still alive. However, there’s not much proof to back this up.

The other story is that the term comes from boxing. The bell would signify the end of a round, “saving” a boxer from losing. This theory is supported by documented evidence. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) notes the earliest use of “saved by the bell” in a 1909 newspaper article about boxing.

Bury the Hatchet

This one has a cool backstory. “Bury the hatchet” comes from an old Native American custom. As part of a peace ceremony, chiefs from feuding tribes would literally bury war axes. Records of this tradition date back to the late 1600s, but it’s likely even older. An Iroquois legend tells how the Five Nations formed an alliance and buried their weapons under a tree to mark the new peace. The phrase, initially used for this ceremony, gradually became a common expression for making peace.

A Chip on One’s Shoulder

This idiom is rooted in the 1800s. Back then, young American boys looking for a fight would place a chip of wood on their shoulder and challenge another boy to knock it off. If the other boy did, it would lead to a physical fight. This custom dates back to at least 1830, when the OED first mentioned it. By the 1850s, the phrase was already being used in its modern sense, meaning someone is holding a grudge or looking for a fight.

God Bless You

The phrase “God bless you” has several possible origins. One story says that sneezing made a person vulnerable to evil spirits, and blessing them would offer protection. Another story attributes it to Pope Gregory I during a bubonic plague outbreak, when sneezing was a symptom. The Pope felt that any divine help was needed and encouraged blessing people when they sneezed. Yet another theory suggests that people believed the heart briefly stopped when sneezing, so blessing someone was either congratulating them on surviving or helping them survive. The true story remains a mystery.

Bite the Bullet

The origin of “bite the bullet” is generally traced back to battlefield medicine. During surgeries, patients would often be given something to bite down on, usually a strip of leather or a bullet. This was meant to make the pain more bearable. Soldiers also bit bullets to prevent crying out during whippings, as silence was considered a point of pride. The earliest use of the idiom listed by the OED is in Rudyard Kipling’s first novel, The Light That Failed, published in 1891.

Hill to Die On

This saying has military roots. Holding the high ground, like a hill, is tactically valuable. A hill is easier to defend because of the improved visibility and the fact that attackers must charge uphill, which is physically draining. The saying refers to something worth fighting and potentially dying for. While some suggest it arose from the Vietnam War, where battles involved claiming hills with heavy losses only to abandon them, there isn’t enough evidence to confirm this.

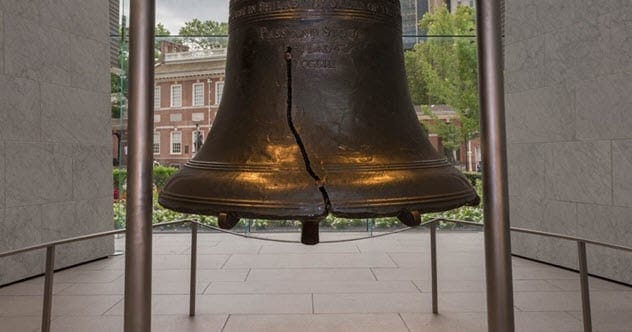

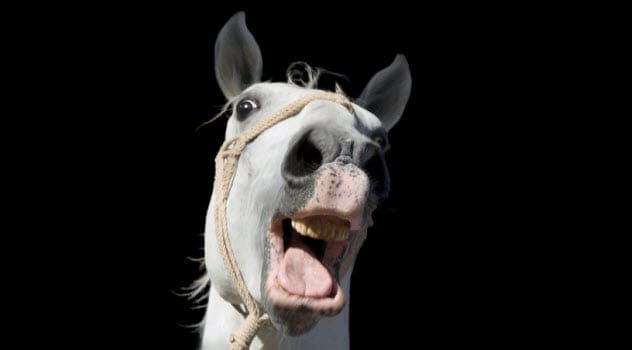

Dead Ringer

Like “saved by the bell,” “dead ringer” is sometimes attributed to fears of premature burial in the 19th century, referring to the person connected to the bell outside the coffin. However, there’s little evidence to support this. The more accepted origin comes from horse racing. “Ringer” was slang for substituting one horse for another to manipulate betting odds. “Dead” in this context means precise or exact, similar to “dead shot.” Thus, a “dead ringer” was an exact substitute, a meaning that has persisted beyond horse racing.

To Hit the Hay

The connection between “hitting hay” and going to bed isn’t obvious, but historical context helps. Mattresses used to be made of hay, straw, or leaves. So, “hitting the hay” meant going to sleep on one of these mattresses. The OED’s earliest record of “hit the hay” is in 1912, but the phrase appears to have been around earlier, as indicated by the absence of apostrophes usually placed around new phrases at the time.

Idioms add color and depth to our language. Understanding their origins not only makes them more comprehensible but also provides a glimpse into the past. From baseball rain checks to battlefield bullets, these phrases tell fascinating stories about where we come from.

Which idiom origin surprised you the most? Leave your comment below!