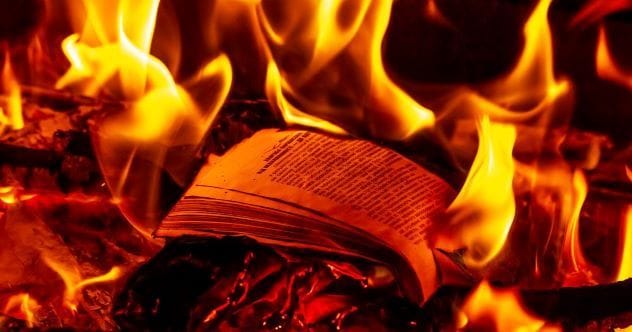

May 10, 1933, stands as one of Western Civilization’s darkest days for free speech. On this grim date, the newly empowered Nazi Party orchestrated a massive burning of books. University students participated, and radio stations across Germany broadcast the event from Bebelplatz, the square by the Berlin Opera House. Around 25,000 books, labeled “un-German,” were thrown into the flames. This act was a chilling attempt to destroy the authors and the ideas they stood for.

Books about peace or communism, writings that questioned German culture or the idea of racial superiority, and anything considered too sexual, all went up in smoke. Of course, books by Jewish authors or those who opposed Hitler were also prime targets. As these ten examples show, the Nazis were practicing their own form of “cancel culture” long before social media existed.

10 All Quiet on the Western Front (Erich Remarque)

Or, as it’s known in German, “Im Westen Nichts Neues.” This title, meaning “In the West, Nothing New,” was penned by Erich Maria Remarque, a German veteran of World War I. Published in 1929, it became an instant classic. The 1930 American movie version was the first film based on a novel to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. The title itself became a common way to describe a situation where nothing changes.

Adolf Hitler, who had served as a Lance Corporal in World War I, was not a fan. He didn’t like focusing on Germany’s defeat unless it fueled his narrative of revenge for the injustices he believed the 1918 Armistice brought upon Germany. In fact, when he conquered France in 1940, Hitler made sure the surrender ceremony happened in the exact same railway car where Germans had surrendered 22 years earlier.

Remarque’s novel didn’t glorify the German soldier. Instead, it highlighted the brutal physical and mental suffering in the trenches of the Great War. It also showed how disconnected many soldiers felt when they returned to civilian life. All Quiet on the Western Front was groundbreaking for its depiction of what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in soldiers, showing the unsettling normalcy of life after conflict.

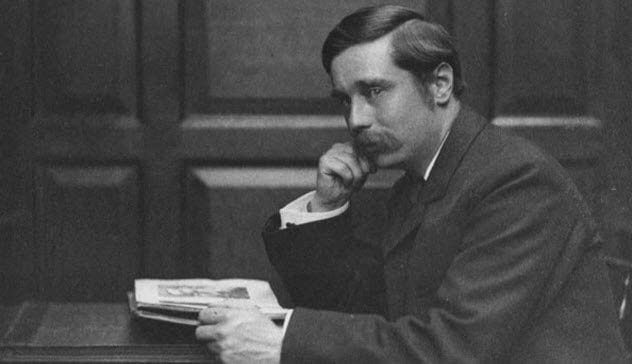

9 The Outline of History (H.G. Wells)

How did a 19th-century science fiction writer end up on Hitler’s burn list? It was because one of his non-fiction books challenged a core belief of Nazi ideology.

While H.G. Wells is famous for classics like The Time Machine (1895), War of the Worlds (1897), and The Invisible Man (1897), his most ambitious work came later. In 1919, he started a series called The Outline of History. With the bold subtitle The Whole Story of Man, this project spanned over 1,300 pages, covering time from Earth’s origins to the then-present day’s Great War.

Wells felt that history textbooks weren’t good enough and believed he could do better. He tried to find common themes in human history, seeing it as a quest for a shared purpose, marked by cycles of nomadic peoples conquering settled societies. He also discussed the growth of “free intelligence,” citing figures like the ancient Greek historian Herodotus.

However, it was Wells’s views on race that destined The Outline of History for the flames. He strongly rejected any ideas of racial or civilizational superiority. He wrote that humans are “an animal species in a state of arrested differentiation and possible admixture,” and that any claim of Western minds being superior simply “dissolves into thin air.”

8 The Metamorphosis (Franz Kafka)

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into an enormous insect.” This unforgettable opening line kicks off The Metamorphosis, a novella that explores themes like the alienating pressures of modern life, the clash between individuality and societal structures, and the often superficial nature of relationships.

The Nazis weren’t keen on these ideas. They promoted selfless devotion to Germany, supported by the concept of racial superiority – the idea that Germans were better than everyone else, justifying struggle and sacrifice for the Fatherland. The Metamorphosis was many things, but it wasn’t a celebration of collective duty in a perfect society.

And, importantly, Franz Kafka was Jewish. Hitler strongly disapproved of Jewish authors.

As Gregor’s family realizes his transformation is permanent, they confine him to his room, remove his treasured possessions, and increasingly shun him. His sister, Grete, is initially the only one who feeds him, but even her loyalty and sympathy eventually fade. Grete transforms from her brother’s sole defender to his main critic, demanding he be removed, which leads him to starve himself to death. Many argue that Grete’s change is the most profound metamorphosis, turning from kind and selfless to cold and practical – qualities society, and perhaps the Nazis, would have valued.

7 Heart of Darkness (Joseph Conrad)

The late 19th century witnessed the Scramble for Africa, a frantic rush by European powers to colonize the continent, often called the Dark Continent. During this period of exploitation, which lasted roughly until World War I, Polish-English writer Joseph Conrad wrote a chilling novel about a journey into the Congo Free State.

Published in 1899, Heart of Darkness follows Charles Marlow, a ferry captain hired by a Belgian trading company to lead an expedition deep into Africa. The further he travels, the more disturbing things become. Early on, he encounters a railroad construction site where African laborers are dying, a stark example of exploitation.

Marlow learns of the enigmatic Mr. Kurtz and treks 200 miles to Central Station, where his riverboat is supposed to be. But it’s wrecked, and repairs take months, during which his fascination with Kurtz grows. Finally, the crew sets off on a two-month journey downriver, only to be attacked by natives just before reaching Kurtz’s Inner Station.

It turns out the natives were protecting Kurtz, whom they worshipped almost as a god, despite (or perhaps because of) his brutal practice of severing their heads and displaying them on posts. The novel’s heavy symbolism was a clear critique of Europe’s racist exploitation of Africa and its people. It’s no surprise Hitler objected to stories highlighting the moral failures of conquest, colonization, and deadly pride.

6 “How I Became a Socialist” (Helen Keller Essay)

The Nazis didn’t just burn books; they also targeted newspapers that printed views opposing Nazi doctrine. One such paper was the New York Call (now defunct), which on November 2, 1912, published an essay by Helen Keller. Keller had become an inspirational figure, overcoming being deaf and blind since infancy.

By 1912, Keller was already well-known. She had published her amazing memoir, The Story of My Life, while still a student at Radcliffe College. The book detailed her incredible journey from being almost unable to communicate to becoming an exceptionally eloquent writer. The next year, she became the first deaf-blind person to graduate from Radcliffe.

As an adult, Keller became a passionate advocate for women’s suffrage, pacifism, and workers’ rights. Her 1912 essay in the New York Call explained her socialist beliefs.

However, Keller’s writings might have been spared if not for another essay published 21 years later. On May 9, 1933—the day before the scheduled mass book burning—Keller published an open letter to German students in The New York Times. “History has taught you nothing if you think you can kill ideas,” Keller wrote. “Tyrants have tried to do that often before, and the ideas have risen up in their might and destroyed them.”

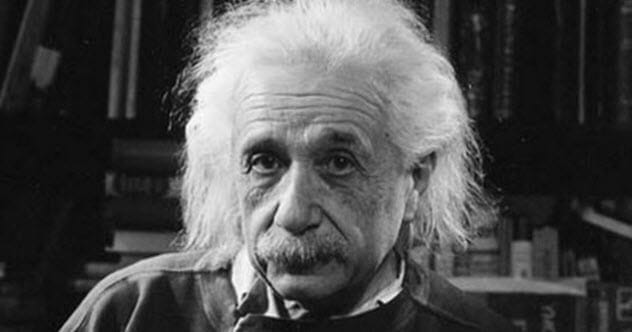

5 Cosmic Religion (Albert Einstein)

In late 1930, one of Germany’s greatest minds was asked about the rising Nazi Party, which had just won over 18% of the vote in parliamentary elections. “I do not enjoy Herr Hitler’s acquaintance,” said the man who would become synonymous with genius. “As soon as economic conditions improve, he will no longer be important.” He also downplayed the party’s strong anti-Semitism, believing that while Jewish solidarity was always needed, a special reaction to the election results was inappropriate.

Even Albert Einstein could be wrong sometimes.

Hitler’s issues with Einstein went beyond his Jewish heritage. If Einstein had stuck purely to academics, his works on the Theory of Relativity probably wouldn’t have been burned. However, Einstein was an outspoken pacifist since 1914, when he refused to sign a document endorsed by many German intellectuals that justified Germany’s militarism before World War I.

Einstein’s views on religion were perhaps even more threatening to Nazi propaganda. In his 1931 work, Cosmic Religion, Einstein revealed that science, not traditional religions, formed the basis of his spirituality. He rejected the idea of a God who intervenes in human affairs—a major problem for the Nazis, as Hitler believed his Third Reich was destined for domination. Luckily, when Hitler came to power in 1933, Einstein was visiting the United States. He decided to stay. Germany’s loss, Adolf.

4 Unnamed Artwork Compilations (Otto Dix)

It’s well known that Hitler considered himself an art enthusiast, if not an expert. As his armies conquered European countries, Hitler looted some of the world’s finest museums, amassing a huge art collection.

Unsurprisingly, if art didn’t meet Hitler’s standards, it was condemned. Many of the books burned at Bebelplatz were collections of works by influential artists (like coffee table books) that Hitler considered improper, too decadent, or harmful to German pride.

One such artist was Otto Dix, a German painter and printmaker known for his brutally honest depictions of war and society during Germany’s post-World War I Weimar Republic. A powerful example is his 1932 panel painting The War, which shows horrific scenes of a devastated city littered with war debris and body parts. Fortunately, the original painting survived; the May 10 burnings mostly targeted printed images, not actual paintings.

Hitler wasn’t finished with Dix, though. In 1933, the Nazis forced him out of his teaching job at the Dresden Academy. Four years later, they featured his work in a Munich exhibition called “Degenerate Art,” meant to show the German public what art should not be in the Third Reich. Despite this, Dix refused to leave Germany and was eventually forced into the Nazi army at the age of 53.

3 A Brave New World (Aldous Huxley)

Apparently, you didn’t mess with Henry Ford if you wanted to stay on Hitler’s good side. Six years before Ford accepted the Grand Cross of the German Eagle—the highest honor the Nazi Party gave to foreigners—he was, in a way, immortalized in English author Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel about a genetically engineered society. Huxley’s futuristic World State revered the famously anti-Semitic automobile tycoon so much that the novel is set in the year AF 632 (After Ford), which is 2540 AD for us. The characters even say “Ford” instead of “Lord,” a clever dig by Huxley.

Even without mocking Hitler’s favorite American, Huxley’s 1932 masterpiece was destined for the bonfire. A Brave New World served as a stark literary warning against groupthink and unchecked power. It featured several technological advancements that Hitler would have undoubtedly desired: genetic engineering in artificial wombs, childhood indoctrination through a rigid caste system, and happiness-inducing drugs to keep the population compliant. This was like a fictional wish list for a Reich intended to last 1,000 years.

Huxley also satirized the arrogance of racism. When his protagonist visits the southwestern United States, they go to a “Savage Reservation” where they encounter the supposed horrors of natural birth and existence, including weaknesses like aging, speaking multiple languages, and religion—in other words, natural humanity itself.

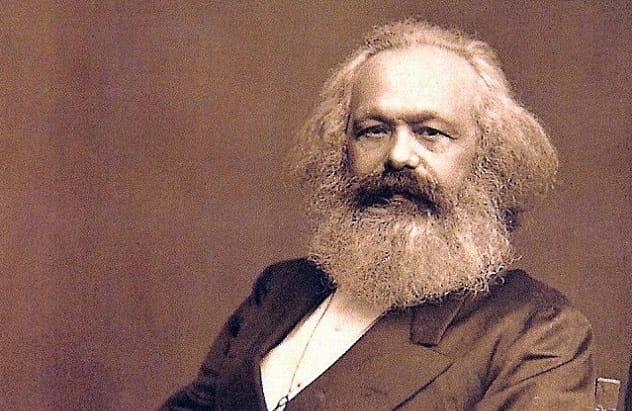

2 The Communist Manifesto (Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels)

It’s common knowledge that Hitler hated communism, but the reasons why are less understood. Considering that Naziism (National Socialist Workers’ Party) claimed to be a socialist movement, the two philosophies actually agreed on several economic issues.

However, Hitler’s hatred of communism—especially Soviet communism—was more personal than political. In the 1920s, Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg introduced him to The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, one of history’s most infamous anti-Semitic forgeries. This fabricated text described Jewish plans for world domination, further fueling Hitler’s existing prejudices.

When you’re as batsh*t nuts as Adolf Hitler, you find enemies everywhere. Noting the significant Jewish involvement in Russia’s 1917–1923 Bolshevik Revolution, Hitler saw it as the beginning of a Jewish takeover of Europe.

Compared to the increasingly twisted interpretations since its 1848 publication, The Communist Manifesto itself is relatively measured. Marx and Engels analyzed society in terms of “Bourgeois and Proletarians”—the upper and working classes—arguing that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” They contended that complacency and divisions among the working class benefit the upper class, as the status quo favors them.

While radical at the time, many of the manifesto’s demands are now common in modern Western societies. These include a progressive income tax, the abolition of child labor, free public education, and substantial publicly owned land.

1 Everything (Institute of Sexology)

Believe it or not, in the early 20th century, Germany was quite progressive in some areas. Founded in 1919 by Magnus Hirschfeld, a renowned expert in the new field of sexology, Germany’s Institute of Sexology was known for its efforts to achieve equality for women and homosexuals. It also did pioneering work in understanding transsexuality. Among other things, Hirschfeld campaigned for the repeal of Paragraph 175, a law that criminalized homosexuality in Germany.

Unsurprisingly, none of this sat well with Hitler. Nor did the fact that Hirschfeld was gay, Jewish, and liberal—a trifecta of traits the Nazis despised. So, on May 6, 1933, four days before the scheduled May 10 mass burning, members of the German Student Union loyal to the Nazi Party invaded and occupied the Institute. They may or may not have received extra credit for this.

Over the next few days, the Institute’s vast collection of texts was hauled to the book-burning site. On May 10, these books became a significant portion of the fire’s gruesome fuel. Hirschfeld was in Paris at the time and learned about the event from a movie theater newsreel. Among the works incinerated was Heinrich Heine’s Almansor, in which the author prophetically wrote: “Where they burn books, in the end, they will burn humans too.”

The burning of these books was a dark omen, a clear sign of the intellectual and physical destruction that the Nazi regime would unleash. The attempt to erase ideas by burning books ultimately failed, as the words and thoughts contained within them continue to resonate and remind us of the importance of freedom of expression.

What are your thoughts on these historical acts of censorship? Leave your comment below and share this post if you believe in the power of ideas.