The Dark Ages, a period often romanticized or misunderstood, holds some truly grim realities. While modern historians have offered nuanced perspectives, archaeological evidence and historical accounts reveal a darker side to this era than many realize. Let’s delve into ten stark reasons why the Dark Ages were, in fact, darker than you might think.

Violence and Bloodshed

The fall of the Western Roman Empire was triggered by violent invasions from Germanic barbarians. These invasions weren’t peaceful accommodations, but brutal seizures of power driven by envy of Rome’s wealth. The chaos led to the empire’s fragmentation and a collapse of the tax base, crippling Rome’s ability to maintain its armies. During the Gothic siege of 410 AD, Romans even resorted to cannibalism to survive. The violence in regions like Gaul lasted nearly a century, marking a truly dark period.

Most of the Empire was Affected

The Dark Ages weren’t confined to a small area; they impacted most of the Roman Empire. While the decline varied in timing and intensity across regions, areas like North Africa, Italy, and Britain suffered significantly. Britain faced a particularly drastic decline, with its Romano-Celtic civilization virtually disappearing, pushing its inhabitants back to a prehistoric way of life. By the 7th century, nearly all territories under Imperial administration, except Constantinople and the Levant, had experienced severe decline.

The Decline of Economic Complexity

The Roman Empire was known for its sophisticated manufacturing and distribution of high-quality goods. However, during the 5th century, political infighting and barbarian invasions decimated regional economies, leading to the disappearance of this economic complexity. By 400 AD, the decline was evident in the West, spreading to the eastern Mediterranean by 600 AD, excluding the Levant. Britain saw the most drastic regression, falling below pre-Roman Iron Age levels. Europe wouldn’t see similar material sophistication again until the Late Middle Ages, between the 13th and 15th centuries.

The Decline of Pottery

One of the clearest signs of decline is seen in pottery. Roman pottery was known for its excellent quality, standardization, mass production, and widespread distribution, benefiting both the rich and the poor. After the Roman period, these characteristics vanished. Pottery production and trade became less sophisticated, virtually disappearing in Britain and parts of Spain. The quality declined, becoming more basic; the amount of pottery decreased, and its distribution from major centers like Roman North Africa became limited.

The Decline of Monumental Building

Housing provides further evidence of decline. During Roman times, even humble dwellings were constructed with mortared stone and brick, featuring tiled roofs. Marble, mosaic flooring, underfloor heating, and piped water were common in both urban and rural homes. In the post-Roman Mediterranean, stone and brick construction declined significantly. Most homes were made of perishable materials like timber walls, dirt floors, and thatched roofs. In Britain, new buildings were made from perishable materials in the 5th and 6th centuries. Even churches required importing artisans from Gaul due to a lack of local expertise.

The Decline of Metalworking

Evidence from Greenland ice caps reveals large-scale metalworking operations during Roman times. Researchers found that lead, copper, and silver smelting were widespread. However, this metalworking significantly declined in the post-Roman period, reverting to prehistoric levels. Roman levels weren’t reached again until the 16th to 17th centuries, around the start of the Industrial Revolution, highlighting a stark regression in technological capabilities.

The Decline of Coinage as a Medium of Exchange

Coinage in gold, silver, and copper was abundant during Roman times, used by both the rich and poor in daily life. In post-Roman Britain, however, the use of coinage almost disappeared. Archaeological sites from this period rarely show evidence of coin usage. In the western Mediterranean, the decline was less dramatic, but copper coins were rarely issued or circulated between the 5th and 7th centuries. The main exception was Rome itself, where copper coins remained in circulation. By the 7th century, even in the eastern Mediterranean (excluding Constantinople and the Levant), coinage had become scarce.

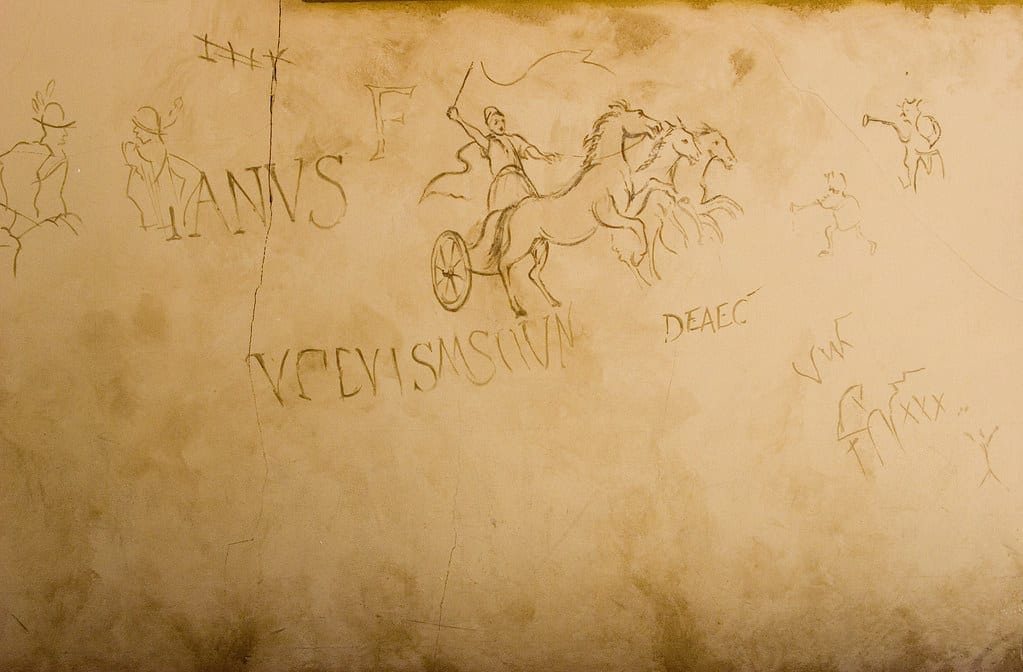

The Decline of Literacy

Reading and writing were widespread in Roman society, evident from inscriptions, graffiti, and the functional literacy needed in the bureaucracy and army. Aristocrats were expected to be well-versed in Greek and Latin literature. However, this changed drastically in the post-Roman period. In Anglo-Saxon Britain, literacy vanished entirely. Commercial and military stamps, seals, and inscriptions became rare in the western Mediterranean. Casual writing, like graffiti, declined as life became simpler and less reliant on the written word. Unlike the literate Roman aristocracy, even rulers like Charlemagne struggled with the Latin alphabet, leaving the clergy as the primary literate group.

The Almost Total Loss of Ancient Learning

By 500 AD, Latin texts were still accessible in Rome and the West, but the transmission of pagan Latin manuscripts virtually ceased in the post-Roman period. The copying of classical texts diminished to the point where the continuity of pagan culture was nearly severed. In the Greek East, economic factors and Christian hostility led to the loss of most pagan literature. It’s estimated that only 1 to 10% of all ancient literature survived the Dark Ages, marking a substantial and unprecedented loss.

The Vanishing Population of Post-Roman Europe

Field surveys north of Rome indicate a sharp decline in rural settlements in the post-Roman period. While buildings made of perishable materials complicate definitive assessments, there’s evidence of declining agricultural output. The size of cows decreased from the Roman period to early medieval times, suggesting a contraction of the food supply. Although tentative, the prevailing evidence suggests declining agricultural productivity and a corresponding decrease in population size across post-Roman Europe.

In summary, the Dark Ages were a period marked by violence, economic regression, loss of knowledge, and population decline. While interpretations may vary, the evidence paints a picture far grimmer than often portrayed. The collapse of Roman infrastructure and societal norms led to a challenging era for those who lived through it.

What are your thoughts on these stark realities? Leave your comment below!