Human desire to conceal is matched only by our desire to reveal. Mystery texts emerge when someone cleverly hides the key to understanding their writing. These texts become popular when the code seems easy to crack. Sometimes the author is alive and holding back information, or the key might be lost in the past.

You might already know some unsolved mystery writings, like the Voynich manuscript and the Phaestos disk, along with treasure-hunt codes like the Kryptos cipher. Now, here are ten more unsolved codes and ciphers filled with supernatural or globalist backstories. Your rewards could include buried treasures, rewrites of history, and even mystical insights.

Faust’s Magic Disc

Dmitri Borgmann, a pioneer in linguistics, cracked many codes but left two unsolved in his book “Beyond Language”. One is a French government formula for pricing funerals, and the other is the mystery text Rembrandt etched into “Faust in His Study, Watching a Magic Disc” (circa 1652). Rembrandt’s glowing disc has “INRI” in the center and “ADAM + TE + DAGERAM / AMRTET + ALGAR + ALGASTNA” around it. This text remains an “indecipherable anagram,” though “INRI” usually represents the inscription on Jesus’ cross.

Borgmann noted the “surely irrelevant” occurrence of AMSTERDAM, Rembrandt’s home, and unconnected Latin anagrams like “ADAM is a cyclic transposal of DAMA (‘fallow-deer’)”. Twentieth-century mystic Samael Aun Weor also used the text for a magic mirror. Borgmann thinks the text came from Rembrandt’s neighbor, Samuel Menasseh ben Israel, who had occult interests. Is ADAM plaintext, or is INRI part of the anagram? Borgmann playfully asks, “Does it inspire you to try your own hand at it?”

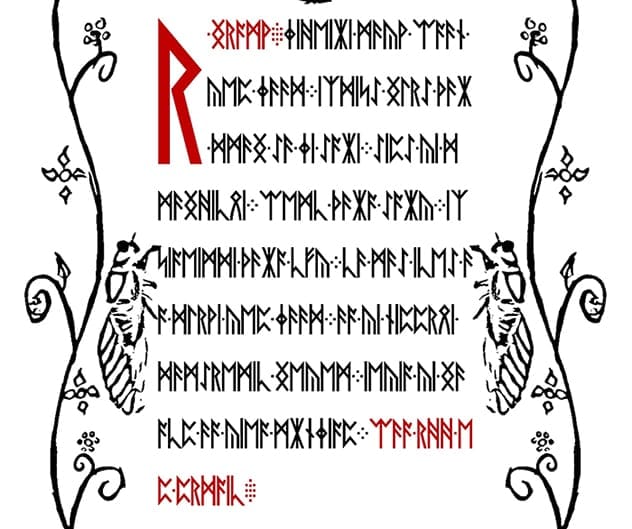

Cicada 3301’s First Book

Cicada 3301 is a controversial, anonymous publisher of challenge data texts. The Washington Post ranked it among the top five “eeriest” internet mysteries. For three years, Cicada 3301 claimed to use complex encryption puzzles to recruit the best codebreakers, the most interested in data privacy. Few successful solvers revealed what they learned, but it seems the “recruits” engineered web privacy tasks.

A Cicada ebook, “Liber Primus” (“First Book” in Latin), was discovered in 2014, written in runes, with cover art of a hand holding a compass. About half the text has been solved, starting with “A warning: Believe nothing from this book”. In 2016, a tweet bearing Cicada 3301’s digital signature stated that “Liber Primus is the way”. The rewards for solving Cicada’s challenges remain unclaimed.

Swift’s Little Languages

Like Edward Elgar, Jonathan Swift often used coding in his work, especially in “Gulliver’s Travels” and “Journal to Stella”. Lemuel Gulliver sounds like “gullible,” and the lands he visits, Lilliput and Brobdingnag, sound like “little” and “big”. Isaac Asimov believed Swift’s “Lindalino” represented Dublin. The word “Yahoo,” now a search engine, is likely a corruption of “Yahweh”.

Much study has gone into Swift’s letters to Esther Johnson, published as “A Journal to Stella”. The letters contain nonce language with phonetic and linguistic changes Swift believed Johnson would understand. Resembling baby talk, this “little language” remains incompletely solved. Swift’s “word-doodling” leaves much new ground to be explored.

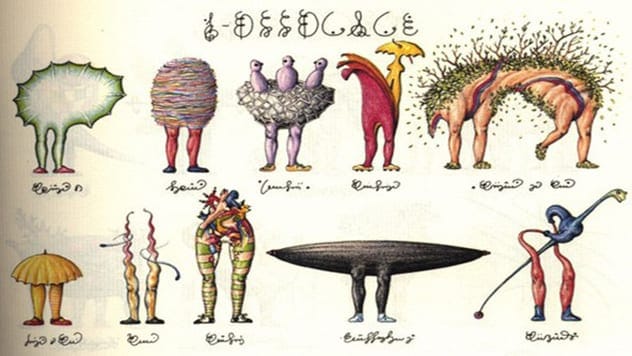

Serafini’s Uncyclopedia

Inspired by the Voynich Manuscript, architect Luigi Serafini handwrote and drew an immense encyclopedic work, published in 1981. Douglas Hofstadter reviewed it in “Metamagical Themas”. The pictures, which Hofstadter called “grotesque and disturbing … beautiful and visionary”, begin with a couple transforming into an alligator.

Serafini later described his work as automatic writing, though regularities like page numbering have been found. Is it just an absurdist fantasy without linguistic content, or does the text have inherent meaning? Readers still debate!

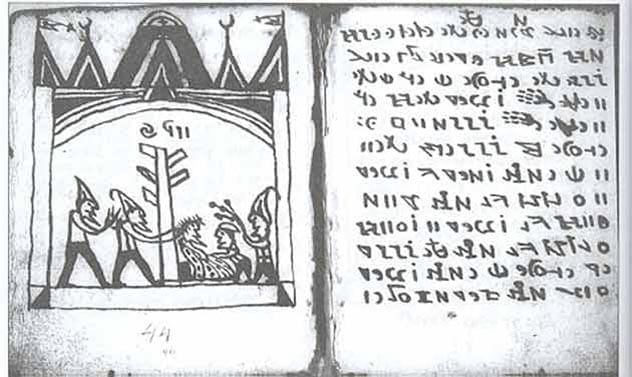

The Holy Codex of Rohonc

By 1838, Count Gusztav Batthyany had many books from around the world at his home, the Castle of Rohonc. He donated many to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, which found a codex of untraceable origin filled with incomprehensible script. Unlike other unsolved codes, the pictures are primitive, and the codes aren’t decorative. The cipher alphabet has at least 100 to 200 characters, often joined together, and the original language is unknown.

A clue might be in the Batthyany library catalog from 1743, which mentions “Hungarian prayers in one volume”. Work by Gabor Tokai and Levente Zoltan Kiraly suggests some characters represent New Testament books and chapters, while illustrations retell the Passion of Christ. Does Rohonc display more “certain piety” than Serafini? Only time will tell.

Hal Gashtan’s Microcosm

“In July 1984 an envelope was placed in the room pictured above …” begins “Microcosm”, a treasure book by “Hal Gashtan”. It promised one thousand pounds to the decoder of the name inside the envelope. Magazines “Creative Computing” and “Your Computer” sponsored this programming contest, thinking it would challenge ’80s PC users. Join phrases from the book’s poetry to 20-letter keys using the provided decryption program to find the phone number and secret name.

The publisher, Lazy Summer Books, underestimated the challenge. Each of thirteen keys requires thirteen correct choices out of sixteen possibilities, before a final combination. Two clues were released: George Washington, and computer names. The 13 computers were found, leading to the text “FIND THIRTEEN NOT ME”. The author disappeared, and the illustrator hasn’t spoken. No internet solve team has succeeded against the mysterious author.

Pink Floyd’s Publius

Pink Floyd’s album “Division Bell” was released in 1984 to promote a world tour. An anonymous persona named Publius proposed on Usenet that the album contained an enigma with a hidden prize. On July 16, 1994, Publius said Pink Floyd would verify the enigma, which happened on the 18th when stage lights displayed “PUBLIUS ENIGMA” during the band’s last U.S. event.

Despite confirmations and hints, no solution appeared, and the puzzle fascinates fans today. Lighting designer Marc Brickman said he programmed the lights under Steve O’Rourke, who gave Brickman’s idea to “some guy of Washington DC … in the encryption game”. Drummer Nick Mason said an EMI Records employee designed the enigma, and the prize was “something like a crop of trees planted in a clear cut area of forest”. Some solutions reference single or double 11s, while PubliusEnigma.blog claims the album refers to herself.

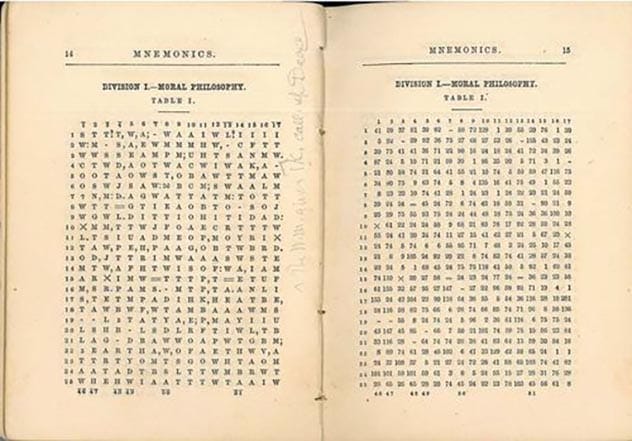

Copious Masonic Mnemonics

In 1981, “Games” magazine asked for help solving an encoded 1860 book, “Written Mnemonics: Illustrated by Copious Examples From Moral Philosophy, Science, and Religion”. It contains letter grids opposite number grids. The “Puzzler”thought it contained Civil War codes but never ran a followup report.

The book is a Masonic ritual cipher. Ray Denslow described the method in detail in “The Masonic Conservators”. The three divisions represented the first three degrees of Freemasons, the letters and numbers were a book code, and the contents chart indicated the rituals. Author Rob Morris created the Conservator movement to keep Masonic lecture texts consistent, but his method was later deprecated. If the book key could be found, an early source of authentic Masonic ritual could be revealed.

Secrets of … Michael Stadther

Inspired by Kit Williams’s “Masquerade”, Michael Stadther published “A Treasure’s Trove” in 2004. Clues led solvers to tokens in fourteen state parks; in 2005, Stadther awarded hunters with jewels worth one million dollars. Solvers anticipated his second book, 2006’s “Secrets of the Alchemist Dar”, with one hundred tokens worth two million dollars.

“The Alchemist Dar” was an anagram of “Michael Stadther”, but the locations remain unclear. Stadther’s company declared bankruptcy in 2007, so no official Dar redemptions occurred. Stadther promised hints until full solution, but these leads haven’t helped. Stadther died in 2018, taking many secrets. Why were Freemason-connected texts in his 2004 book, “100 Puzzles, Clues, Maps, Tantalizing Tales, and Stories of Real Treasure”, if it aimed to help find his hunt clues?

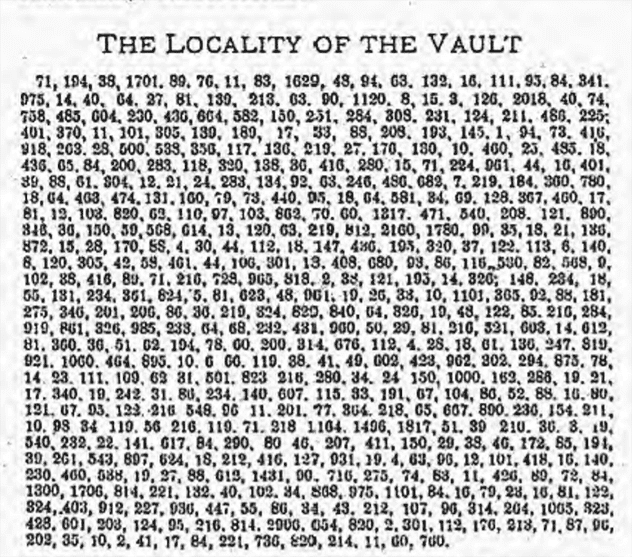

Cole’s Solution to Beale’s Cipher

In 1885, James B. Ward published “The Beale Papers”, telling the story of Thomas J. Beale, who hid gold and silver in Bedford County, Virginia, in the 1820s. It contained three ciphertexts, one of which was solved using the Declaration of Independence, describing the treasure. The other two, unsolved, described location and heirs. Jim Gillogly noted improbable alphabetic sequences in cipher one, suggesting a hoax or additional decryption layers.

The website BealeSolved claimed the vault was found in 2001, presenting solutions to ciphers one and three, but said nothing remained. However, the solutions weren’t book ciphers, as identical numbers yielded different plaintext, and no method was given. Solver Daniel Cole died during the hunt in 2001. Cole and fellow hunter Gary Hutchinson shared a Masonic background. The BealeSolved site was created by SWN, likely Steven Ninichuck, who told Michael Stadther they solved everything but were beaten to the punch. Why did Ninichuck post an unverifiable solution, and why did Stadther say the solution was “deciphered … from a Masonic ritual”?

These unsolved coded mysteries offer a fascinating glimpse into the human desire to conceal and reveal. From magic discs to Masonic rituals, each code holds the potential for discovery and insight. Will you be the one to crack them?

Leave your comment below and share your thoughts on these mysteries!