Ever since the publication of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, a murder mystery set in the Middle Ages, the medieval detective story has grown in popularity. Of course, there were no detectives in our modern sense during the Middle Ages.

However, the idea of solving crimes through observation, experience, and knowledge fascinates readers used to modern crime-solving with fingerprints and DNA. But what was crime investigation in the Middle Ages really like?

A Violent Age

Today, we describe a gruesome attack as “going medieval.” Though the Middle Ages were no more brutal than today, we are still shocked by the violence, even in times of peace.

Homicide rates in England were 10 times higher than today. Records show half of all murders resulted from simple arguments. Only some Italian city-states had law enforcers. Most murderers fled and were never caught. However, there was little of modern America’s serial killers. Only Gilles de Rais, Joan of Arc’s lieutenant, who abused and murdered over 100 boys, stands out.

The Church, which should have been a refuge, sanctioned torture and execution for heretics and taught St. Augustine’s rationale for “just war”—holy violence to enforce moral conformity. A priest even preached approvingly of a man killing his adulterous wife and her lover. In Iceland, revenge killing was legal. Italy struggled to regulate personal vendettas.

Killers often went unpunished. Claims of self-defense and hot-blooded passion led to acquittal. Some prisoners bribed authorities, and others joined religious orders to escape courts. Only 12 to 20 percent of homicide cases ended in conviction. Medieval society was full of free murderers.

Compurgation

Finding a criminal relied more on superstition than fact. The belief that God punishes the guilty and protects the innocent led to procedures to uncover God’s judgment. Someone accused of a crime could gather people to swear to their innocence, called compurgation or trial by oath.

The number of oath-takers varied. Queen Uta, accused of adultery in 899, was cleared by 82 knights. A Welshman charged with poisoning needed 600 compurgators. Compurgation persisted until the 16th century.

If one couldn’t find compurgators, they could be tried by ordeal, like a lie detector. The most common were fire and water ordeals. In fire, a suspect carried a red-hot iron for 9 feet. If the wound healed within three days, they were innocent. In water, the accused was thrown into a river. If they sank, they were accepted by God; if they floated, they were guilty.

Trials by ordeal didn’t sit well with the Church, which forbade priests from blessing the iron and water in 1215. In 1219, King Henry III decreed the jury, which previously decided who underwent the ordeal, now determined guilt through evidence. Medieval justice had leaped forward.

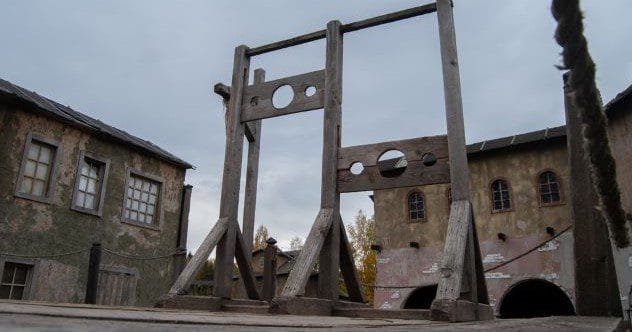

The Law of Torture

Torture was used in the Middle Ages to get confessions, but judicial torture had rules to ensure the confession was reliable. When trials by ordeal were banned in 1215, jurists looked for a way to replace the absolute proof with judgment by humans instead of God.

The system required two eyewitnesses for conviction, or the accused’s voluntary confession. Circumstantial evidence wasn’t enough. Only if the suspect was seen killing the victim could they be judged guilty.

In the desire for certainty, jurists set the bar too high, making it easy to get away with murder. Voluntary confession was the only way to get a conviction in clandestine crimes. Judges wanted torture only for those most likely guilty.

To obtain probable cause for torture, there must be “half-proof,” like one eyewitness, or finding the murder weapon (1/4 proof) and loot (1/4 proof) in the suspect’s possession. Confessions obtained by torture were “voluntary” only if repeated in court. Confessions also needed corroborating evidence.

Torture wasn’t used without restraint. While historian Michel Foucault said medieval Europe was “the country of tortures,” judicial torture gradually fell out of favor and ended in the 18th century as more humane methods developed.

Ordeal of the Bier

The Ordeal of the Bier, or cruentation, survived to the late 17th century. Ancients believed the dead were conscious and could show indignation in the presence of their murderer. The killer’s touch would cause the corpse’s blood to flow.

In the Middle Ages, a slain victim was laid naked, and the suspect approached the body, calling out its name. The suspect circled the body, stroking its wounds. If fresh bleeding appeared, or the mouth foamed, or the body moved, the suspect was guilty. Sometimes, the entire community had to pass by the body. Cruentation persisted as late as 1688 when it was accepted as evidence by an Edinburgh High Court.

The modern practice of viewing the body may have originated in the Ordeal of the Bier.

Hue and Cry

Calling the cops wasn’t an option. In England, the person who found the corpse was called the “First Finder.” They had to raise the “hue and cry,” screaming to call the neighbors. In close-knit communities, a suspect might be identified quickly. A First Finder who didn’t get involved risked a fine.

The neighbors arrested the suspect and looked for evidence. If the suspect fled, they had to pursue him. If he resisted, they could kill him. If he submitted, he was bound for trial, and a jury was elected from the people who knew him to investigate the case.

Sheriffs and Coroners

The sheriff and the coroner were responsible for law enforcement. The sheriff (shire reeve) was the closest thing to a police detective. He investigated crimes and could form a “posse comitatus” to hunt fugitives, a group of local men over 15 conscripted by the sheriff. The sheriff worked with the coroner (from “corona,” meaning crown) who found the cause of suspicious death.

Assisting the coroner was a jury of 12 to 24 men from the neighborhood. They questioned witnesses and gathered clues at the crime scene. The jury’s findings were recorded on coroner’s rolls, specifying the time, location, names, events, weapon, and the nature of the wound. The coroner jury’s verdict was crucial in informing the trial jury’s vote.

Autopsies

The first recorded autopsy was on Julius Caesar in 44 BC by Antistius, who found the fatal blow had ruptured the aorta.

English coroners couldn’t perform autopsies. They weren’t physicians and had to consult outside experts. But even they couldn’t open up a body; Northern Europeans believed the soul separated slowly from the body, and autopsies were taboo.

On the Continent, especially in Italy, autopsies were regularly performed by medical professionals to investigate suspicious deaths. The first forensic autopsy was by Bartolomeo Varignana in 1302. Reliance on expert testimony put Continental forensic science ahead of England’s.

The Knight Detective

In November 1407, Louis, Duc de Orleans, was ambushed by assassins on a Paris street. The job of finding the killers fell to Guillaume de Tignonville, the Provost of Paris. Though a knight, de Tignonville may be one of the first true detectives.

De Tignonville rushed to the crime scene, ordering city gates closed. He examined the body and had officers investigate a nearby house the killers had used. He and his men interviewed witnesses to piece together what happened. The broker who rented the house and vendors who sold goods provided information.

A picture of a conspiracy emerged, and de Tignonville dared powerful men to open their chateaux for searches. The conspirators were unmasked, including a royal family member who had lamented at Louis’s funeral. This case was solved without torture, instead relying on physical evidence and interviews, the same procedures used by modern police. Guillaume de Tignonville was ahead of his time.

The Father of Forensic Science

While European law floundered, in Sung Dynasty China, Song Ci published a manual for coroners assessing suspicious deaths, The Washing Away of Wrongs, addressing the cause and time of death, injuries, and decomposition.

Here are some of Song’s observations:

Death by suffocation: “From the mouth and nose, a clear bloody fluid will flow…the bowels will protrude.” Beheading: “If the head is cut off a corpse, the neck will be long. There will be no contraction.” Burning: “When a living person is burned to death, there will be sooty ashes in the mouth and nose… If the burning occurred after death… there will be no sooty ash.”

Song even had a version of Luminol: “On the cleaned spot where the corpse has been, sprinkle a thick decoction of rice… If the victim was murdered there, the spot where blood soaked into the ground will be fresh red.” He recommended covering the body with mashed white plums to discover latent injuries and used diagrams of the human body to pinpoint injuries.

While Song Ci’s manual accepted some folk beliefs, its methods guided Chinese law enforcement for centuries. Song can be called the Father of Modern Forensics.

The Case of the Bloody Sickle

In 1235, Song investigated the murder of a peasant in a rural village, found hacked to death. By testing blades on an animal carcass, Song concluded the murder weapon was a sickle, indicating the killer was a fellow peasant.

Song ordered the ten or so villagers who owned sickles to lay them out in the sun. Flies began to buzz over one sickle, attracted to the residual blood. Faced with this evidence, the owner confessed.

This is the first murder case solved by forensic entomology. In his manual, Song also described telling the time of death from maggots. All this was nearly 800 years ago.

Medieval crime investigation was a mix of superstition, brutality, and surprisingly modern techniques. From trials by ordeal to the brilliance of figures like Guillaume de Tignonville and Song Ci, the quest for justice in the Middle Ages offers a fascinating glimpse into the past.

Leave your comment below to share which fact surprised you the most!