The history of the natural world is ingeniously written in genetic code. At times, snippets of this code bravely face cataclysms and the relentless march of time to deliver truth safely to scientists. More often than not, what DNA reveals about the past is so peculiar that it stretches the limits of belief.

Genes aren’t just bearers of delightful news; some carry the footprints of epidemics and human cruelty, while others plunge existing theories into uncharted mysteries. DNA can become downright disturbing when its origins and effects on the human mind are examined.

Mysterious Tame Horses

The story of the first domesticated horses remains shrouded in mystery. It was widely believed that around 5,500 years ago in Kazakhstan, some animals were lassoed and broken in for riding.

Horsemanship in the Botai culture, credited with domesticating horses, isn’t just a myth. Ancient remains at Botai sites include equine teeth showing signs of bridles and fat from horse meat and milk. These were thought to be the first tamed horses. However, recent DNA tests on 88 ancient and modern horses have shattered some long-held beliefs.

The first revelation was that modern horses have too little Botai influence to have descended from Kazakhstan’s horses. This suggests the existence of an unknown domesticated ancestor. Currently, scientists can only speculate about their characteristics.

The second belief challenged involved Earth’s last remaining wild horses – Przewalski’s horses. This Mongolian breed was previously thought to have originated in the wild. The tests, however, indicated that they descended from the already-domesticated Botai herds before turning feral. Intriguingly, the DNA also revealed that the Botai horses had striking white coats with spots.

An Exiled Nation That Stayed

Before the Spanish decimated the Inca civilization, the Inca themselves recounted how they destroyed the people of Chachapoyas. The Chachapoyas had resisted the Inca invasion of their region in Peru. Spanish records detailed how they were driven out in the 15th century.

In 2017, scientists analyzed samples from modern inhabitants of Chachapoyas, revealing the Inca claim to be exaggerated. Among those tested were living descendants of the Chachapoyas. The Inca conquered, but did not completely displace the Chachapoyas people.

Another notable trait emerged: the Chachapoyas remained genetically distinct, suggesting a refusal to mix with the Europeans or even the Inca. Genetic tests followed a linguist’s discovery that some individuals still spoke Quechua, a language thought locally extinct. Quechua, spoken by millions elsewhere, predates Columbus. The rare Chachapoyas dialect closely resembled Quechua from Ecuador. However, DNA analyses found no common link to explain this similarity.

Great-Great-Grandson Of Neanderthal

The story of an ancient human bone discovered in Romania revealed an intriguing ancestry. The jawbone, named Oase 1, was unearthed in 2002 from a cave in Pestera cu Oase.

The relic yielded an incomplete genome, yet it showed nearly 10 percent Neanderthal DNA. Today, individuals typically measure less than 4 percent. This made Oase 1 an unprecedented find.

It’s known that humans and Neanderthals interbred, but the specifics are elusive. This man, who lived thousands of years ago, provides evidence that interbreeding began soon after humans arrived in Europe, challenging theories suggesting a later merger.

This ancient Romanian is a rare individual genetically close to this interbreeding. With such a high percentage of Neanderthal genome, he may have had a Neanderthal ancestor as recently as a great-great-grandparent. Oase 1 is uniquely extinct—the Neanderthals disappeared around 39,000 years ago, and his human lineage has no living counterparts.

The Agent Behind Cocoliztli

Between 1545 and 1550, a devastating illness known as the cocoliztli epidemic swept through Mexico and Guatemala, claiming countless lives. Suspicion fell on the Spaniards, who had arrived in Mesoamerica shortly before the outbreak. It was assumed they brought a disease to which the locals had no immunity.

To identify whether the disease was smallpox or measles, scientists examined a cemetery in Oaxaca abandoned after the epidemic. Remains from 29 graves were analyzed using technology to search for germ DNA.

Surprisingly, the usual suspects were absent. Instead, the deadly Salmonella bacterium was identified in 10 individuals. The bug’s genome was reconstructed and identified as S. paratyphi C, a subspecies causing enteric fever, including typhoid.

Salmonella poisoning is spread through contaminated food and water. Globally, around 222,000 typhoid-related deaths are reported each year. These 10 ancient patients represent the first evidence of Salmonella in the New World, offering a rare glimpse into the disease’s history.

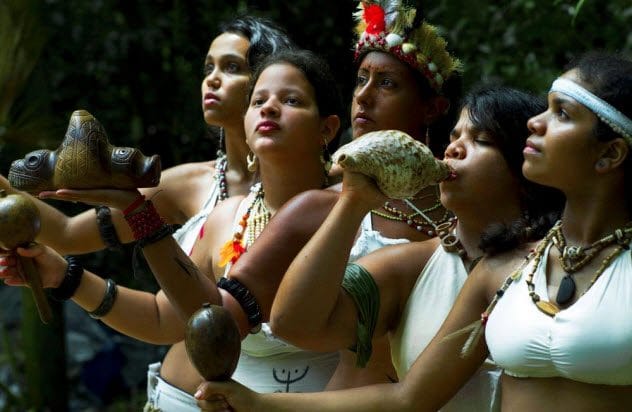

Taino DNA

While Europeans are no longer blamed for the cocoliztli epidemic, the Caribbean tells a different story. Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the 15th century heralded immense suffering for the indigenous Taino people. Those not enslaved faced new epidemics and widespread slaughter.

The impact was so extensive that historians declared the Taino population extinct, sidelining modern individuals in the Caribbean who claimed Taino heritage.

To resolve this, DNA from a pre-Columbian islander was needed. In 2018, a study confirmed this heritage. A thousand-year-old tooth from a woman in the Bahamas provided undeniable Taino DNA that matched living populations in the Caribbean, particularly in Puerto Rico.

Beyond proving their survival, the woman’s genes indicated South American roots and interconnected communities, explaining the lack of inbreeding despite the small island setting.

The Minoans’ Ethnicity

Sir Arthur Evans discovered the Minoan palace of Knossos in Crete about a century ago. Noting the Egyptian-like art, Evans theorized the Minoan culture originated in Africa, an idea that persisted. Though much about the Minoans remains mysterious, they are credited with establishing Europe’s first advanced civilization (2700 BC–1420 BC).

In 2013, DNA was extracted from Minoan skeletons and compared to samples from both ancient and modern populations in Africa and Europe. The results debunked Evans’ theory.

The Minoans were not from Egypt or Africa, but rather were European. They most closely resembled Stone Age Europeans, with the closest living relatives being the islanders of Crete, particularly those from the Lassithi Plateau, where the skeletons were found.

This shows that the Minoans were indigenous to the region. Contact with Africa likely influenced their art.

Matriarchs Of Chaco Canyon

In the arid southwest of North America, a mysterious culture thrived. From AD 800–1130, they erected intricate structures in Chaco Canyon. While many discoveries have illuminated aspects of this long-gone society, a complete understanding remains elusive.

The society was notably complex, exhibiting an elite class, but the criteria for achieving such status remained unclear.

The largest building, Pueblo Bonito, contained a crypt holding nine individuals who enjoyed elite status during their lives and were buried over 330 years (AD 800–1130). Genetic sequencing in 2017 revealed a surprising connection: they were related and shared identical mitochondrial DNA, passed down exclusively from the mother.

The unbroken female line across generations suggests that the ruling dynasty of Chaco inherited power through the maternal line.

Death Of A King

In 2013, a journalist acquired blood-stained leaves linked to King Albert I, a passionate mountaineer, at an auction.

In 1934, the 58-year-old Belgian monarch died in a climbing accident. His body was found at the base of a cliff near Marche-les-Dames. The area was soon stripped bare by souvenir hunters.

In 2016, the journalist had the leaves tested, comparing the DNA to that of King Albert I’s relatives, Baroness Anna Maria Freifrau von Haxthausen and King Simeon II of Bulgaria. The DNA matched.

While the blood’s authenticity was confirmed, the cause of death remains debated. The presence of the King’s blood, however, debunked a conspiracy theory suggesting he was murdered elsewhere and moved to the site.

Cheddar Man

The remains of Cheddar Man were discovered in 1903 in Cheddar Gorge. Dying young in his twenties, he represents Britain’s oldest complete human remains at 10,000 years old.

Researchers reconstructed his skull and analyzed his genome to determine his eye and skin color.

Cheddar Man’s DNA revealed he had blue eyes and dark brown to black skin. His hair was also dark with a slight curl. While startling to modern beholders, these features were commonplace in Western Europe during his lifetime.

A landmass once connected Europe to Britain, and Cheddar Man likely came from migrants who resettled the island 11,000 years ago. This population was eventually absorbed by pale-skinned farmers from the Middle East around 6,000 years ago. When his mitochondrial DNA was compared with people living in Cheddar village today, a match was found in two residents.

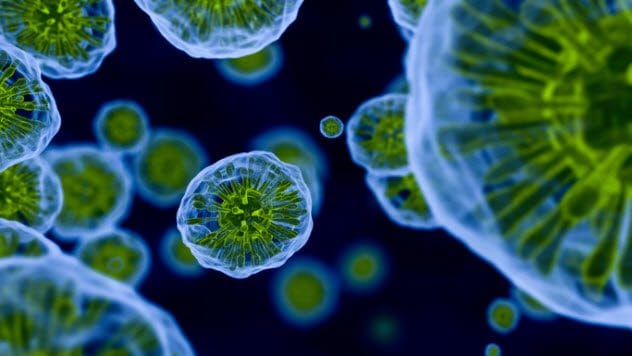

The Mind Virus

A 2018 study revealed unsettling news: humans may owe conscious thought to a virus. Between 40 and 80 percent of the human genome is composed of DNA left by ancient viruses.

This is generally harmless and often beneficial. Viral genes play a vital role in embryo development and the immune system. The game-changer is the Arc gene, a genetic parasite that entered the brains of four-legged animals long ago. It merged its code with the host genome and remains active in human brains.

When a synapse fires, Arc transmits genetic information between nerve cells in packages that resemble viruses. Although how Arc invaded people and animals or what happens when its genetic “mail” enters another cell is unknown, Arc’s activity maintains nerve communication and adaptation, both vital for conscious thought.

It may sound unsettling to host a living ancient virus in one’s brain, but without it, synapses would shrink, and cognition would be affected. A defective Arc gene has been linked to neurological disorders, including autism.

Ancient DNA tests have opened incredible new windows into the past, challenging long-held beliefs and revealing surprising truths about the history of humans and the world around us. From rewriting migration patterns to unearthing the causes of ancient epidemics, these remarkable discoveries highlight the crucial role of genetic research in understanding our origins.

What do you think is the most fascinating discovery on this list? Share your thoughts in the comments below!