The line between life and death has always fascinated and, at times, horrified us. Tales of severed heads showing signs of awareness have fueled both nightmares and scientific inquiry. Think of Anne Boleyn’s rumored post-execution lip movements or Charlotte Corday’s flushed face after her executioner’s slap. These accounts blurred the boundary, inspiring horror movies and, more importantly, pushing scientists to explore the very limits of brain survival.

This list dives into the groundbreaking, and sometimes disturbing, work of ten scientists who managed to keep brains alive outside the body, challenging our understanding of life, death, and consciousness.

10. Charles-Édouard Brown-Sequard

Charles-Édouard Brown-Sequard (1817–1894) was a brilliant, albeit eccentric, scientist. His experiments, while sometimes bizarre, significantly contributed to our understanding of physiology.

In an 1857 experiment, Brown-Sequard delivered fibrin-free, oxygen-rich blood to a decapitated dog’s head. This process, called perfusion, seemingly reversed rigor mortis. According to Alex Boese, the head displayed “voluntary movements in the eyes and face” and “tremors of anguish” before finally succumbing again. This experiment ignited discussions about the possibility of restoring life to deceased organs.[1]

9. Jean-Baptiste Vincent Laborde

Jean-Baptiste Vincent Laborde (1830–1903) mirrored Brown-Sequard’s work, but with a darker twist: human heads. Laborde bribed his way to obtain the head of a recently guillotined criminal. He then perfused the head’s blood vessels with oxygenated cow blood.

The results were unsettling. The criminal’s face contorted, his tongue appeared to “boil,” and his jaw snapped shut. While whether this animation indicated awareness remained controversial, it fueled debates about consciousness after decapitation. French physician Gabriel Beaurieux even claimed to have witnessed a guillotined prisoner’s eyes focus on him after calling out the man’s name.[2]

8. Corneille Heymans

Corneille Heymans (1892–1968) won the Nobel Prize in 1939 for his work on respiration regulation. However, the specifics of his experiments were, to say the least, unconventional.

Heymans surgically connected the head of a decapitated dog to a live dog, creating a shared physiological system. The live dog supplied blood to the severed head. This experiment demonstrated a feedback loop, independent of blood-borne chemicals, responsible for the vagus nerve’s reflex arc traffic. Heymans’s work, while ethically questionable, provided crucial insights into neurological functions.[3]

7. Vladimir Demikhov

Vladimir Demikhov (1916–1998), a Soviet surgeon, shocked the world with his surgical creations. One of his most infamous experiments involved grafting the head and forelegs of a puppy onto a full-grown dog.

Demikhov’s two-headed dog became a symbol of both surgical innovation and ethical concerns. The puppy’s head retained its personality, even biting the host dog. While the hybrid animal only survived for six days, Demikhov’s work aimed to understand organ replacement and the potential for mechanical substitutes.[4]

6. Robert J. White

Neurosurgeon Robert J. White (1926-2010) pushed the boundaries of transplantation by transplanting the head of one monkey onto the body of another. This groundbreaking surgery sparked both praise and condemnation.

White’s research focused on how a body reacts to a new brain. The monkey, after regaining consciousness, could see, hear, smell, and even bite, but it couldn’t move its new body. White’s techniques, which involved lowering the body’s temperature to protect the brain during surgery, were revolutionary, even though they raised significant ethical questions.[5]

5. Rudolfo Llinás

Rudolfo Llinás and his team achieved a significant breakthrough in 1993 by isolating an adult guinea pig’s brain outside its body. They immersed the brain in a fluid that sustained its life for eight hours.

Analysis of nerve impulses showed that the brain’s electrical signals closely resembled those of a living animal. This experiment proved the viability of studying mammalian brains and their complex circuits in isolation, opening new avenues for neurological research.[6]

4. Anton Coenen

Anton Coenen co-authored a study examining the effects of decapitation on rats. The researchers aimed to determine if decapitation was a humane euthanasia method by measuring brain activity via electroencephalogram (EEG).

The study suggested that consciousness vanished within three to four seconds after decapitation, implying it was a quick and relatively humane method, even if death itself took nearly a minute. A “wave of death” was observed on the EEG about one minute after decapitation, marking the synchronous death of brain neurons. This study’s implications extend to discussions about organ donation timing.[7]

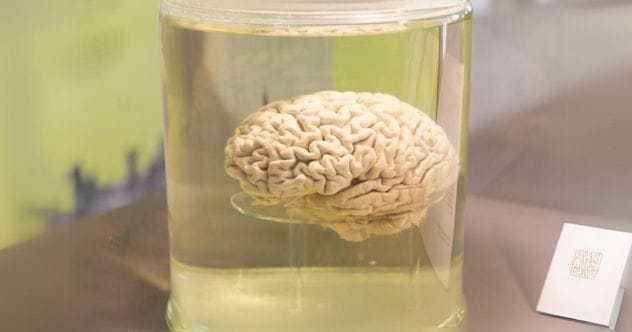

3. Nenad Sestan

Yale University neuroscientist Nenad Sestan and his team explored the possibilities of restoring circulation to severed pig heads obtained from a slaughterhouse. They used a system of pumps, heaters, and artificial blood to revive the heads.

While the pig brains didn’t regain consciousness, billions of individual cells were found to be healthy and capable of normal activity, indicating that the brains remained alive. Sestan highlighted the ethical implications, noting that a reanimated brain would be in “the ultimate sensory deprivation chamber.”[8]

2. Juan M. Pascual

Juan M. Pascual, a Professor of Neurology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, conducted experiments on sedated pigs to study neurophysiological mechanisms and synaptic function in their brains, which are similar to human brains.

The EEG recordings of the pigs’ brains were remarkably similar to those of awake humans, suggesting that the physiological processes in pig brains might not differ significantly from human brains. This research provided valuable insights into brain function.[9]

1. University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Building on Pascual’s research, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center developed a device that isolates blood flow to the brain, allowing it to survive and function apart from the body for several hours.

This device enables researchers to study the brain independently of the body. They’ve used it to better understand the effects of hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) without the complicating factors of altered metabolism. This innovation opens up possibilities for designing better cardiopulmonary machines and advancing brain research.[10]

The scientists on this list have pushed the boundaries of what we thought possible, venturing into ethically complex and scientifically fascinating territory. Their experiments, while sometimes unsettling, provide invaluable insights into the workings of the brain and challenge our understanding of life and death.

What do you think about these experiments? Share your thoughts in the comments below!