The phrase ‘witch hunt’ brings to mind images of superstition and irrational cruelty from the early modern period. Yet, witch beliefs and persecutions are often misunderstood. For example, it’s a common misconception that Puritans were the primary witch burners, or that witches were frequently burned in England and America. Similarly, the Middle Ages saw fewer witch accusations compared to the Shakespearean era or ancient Rome. Even after the British Witchcraft Act of 1736, popular beliefs and violence against alleged witches persisted well into the 20th century.

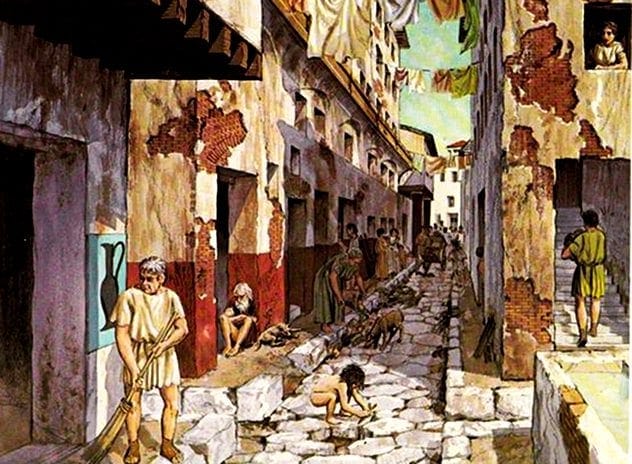

The Romans and Witchcraft Beliefs

Belief in witchcraft is ancient, tracing back to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Surprisingly, the fear of witchcraft was potent in Ancient Rome, a society known for order and rationality. This paradox mirrors early modern Europe, where witch hunts occurred alongside significant achievements in art, science, and literature.

Historically, witches were scapegoats for natural disasters, crop failures, and diseases. During a Roman epidemic in 331 BC, over 170 women were executed for magic. Between 184-180 BC, thousands of supposed black magicians were killed in response to epidemics across Italy.

Clairvoyance Among Witches

Between 1450 and 1750, around 110,000 people were tried as witches, with about 60,000 executed due to superstition and misogyny. However, some evidence suggests that a few accused witches possessed genuine psychic powers.

In Scotland in 1591, Agnes Sampson was interrogated for witchcraft. King James VI was skeptical until Sampson accurately recounted a private conversation between him and his wife. Impressed, James began to take her claims seriously. Modern mediums and even the CIA use remote viewing and clairvoyance. Sampson was later executed, marking the start of a British witch craze that James I brought to England in 1603.

The Witch of Edmonton’s Tragic Tale

On April 14, 1621, Elizabeth Sawyer of Edmonton was charged with witchcraft and hanged. A key piece of evidence was the death of Agnes Ratcliffe, a neighbor, after an argument with Sawyer. Ratcliffe’s husband claimed Sawyer cursed his wife, who died soon after, foaming at the mouth.

The case inspired a play by Thomas Dekker, William Rowley, and John Ford. While audiences were drawn by the story’s wonder and terror, others recognized the real villains were those who ostracized Sawyer, driving her to the Devil and his dog. Modern viewers may find the scenes between Sawyer and the devil dog poignant or absurd.

Witch Cannibals: A Dark Taboo

Witches were often accused of cannibalism, particularly of eating babies or children. They were said to rob graves and grind bones for magic, driven by a lust for human flesh. Lyndal Roper mentions Barbara Lierheimer’s 1590 confession of eating “a roasted child’s little foot.” Despite Lierheimer’s torture, she and others were believed to secretly eat children.

In 1611, Louis Gaufridi, a male witch, was burned in Aix-en-Provence. He never touched his food, claiming he ate “good flesh, the bodies of infants invisibly sent…from the synagogue.” Gaufridi and his coven were accused of eating and strangling infants, and using corpses to make pies.

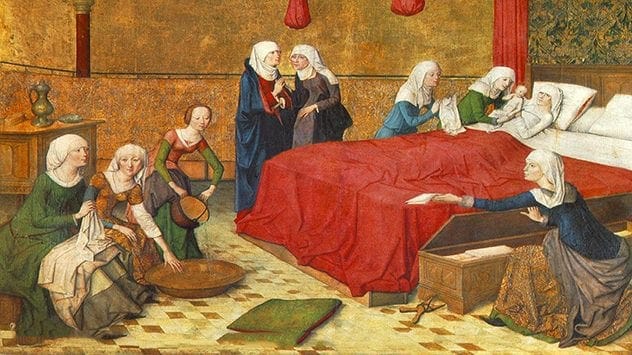

Sucking Out Your Life Force

A common belief was that witches attacked life by causing miscarriages, infertility, and cot deaths. They were also blamed for severe weather affecting crops and livestock. Witches were thought to suck the life from food, animals, and people.

In 1612, Ellen and Jennet Bierley were accused of killing an infant by occult means, roasting and eating parts of it, and using the fat to transform themselves. Jennet Bierley supposedly sucked the child’s soul. In Mexico in 1888, a man was tried for murdering a witch who allegedly demanded “protection money” from parents, threatening to suck the breath from their children.

Male Witches: An Uncommon Phenomenon

About 80% of witchcraft accusations targeted women, but Normandy had a high number of male witch cases from 1564-1660. William Monter notes that men dominated Norman witchcraft cases after 1630. In Essex, England, two notable “male witches” had distinct lives.

In 1864, Emma Smith and Samuel Stammers were jailed for assaulting a deaf-mute fortune teller, believing he had bewitched them. Meanwhile, George Pickingale of Canewdon, Essex, lived until 1909, feared for his supposed ability to stop farm machinery and control familiars. Pickingale was also a healer and possibly clairvoyant.

Cutting a Witch to Break Their Power

Spontaneous attacks on alleged witches were driven by terror or personal feuds. “Cutting a witch” was a tactic based on the magical idea that it would negate the witch’s power. In Scotland, this meant cutting the witch on the forehead.

In 1706, Reverend Peter Rae cut a woman believed to have bewitched him. In 1826, a minister sewed up the forehead of a woman accused of drowning a miller’s pigs. In 1842, a brickmaker named Radley, convinced his health problems were caused by a witch, cut her arm in the street; the woman was Radley’s mother.

Child-Witches: Victims and Accusers

While children dressed as witches are cute today, this would have horrified parents in past centuries. Children were usually the victims of witchcraft, but sometimes they were identified as witches themselves. Over 40 children were executed as witches in Wurzburg in the 1620s.

In 1669, a terror swept through the Swedish village of Mohra, with interrogations revealing 300 children claimed to attend Witches’ Sabbaths. Fifteen children were executed, and 148 were whipped. In Augsburg in 1723, children were accused of attending Sabbaths and putting diabolic powder in their parents’ beds, leading to imprisonment.

The Witch Dynasty of Dettingen

Many believed that devilish magic was inherited. In Dettingen, the Gamperle family was known as career witches and serial killers. Paul and Anne Gamperle, along with their sons and associates, formed a coven. During a black rite in 1600, a dog disturbed them, leading to their confessions.

Paul claimed to have murdered 100 children, two uncles, and sixteen neighbors. Anne admitted to killing 100 children and nineteen old people. The sons claimed to have jointly killed over a hundred. The coven’s total was 527 murders. They were brutally executed, with Anne’s breasts cut off and the family burned alive.

Witches and Poltergeists: Unseen Forces

Poltergeists, disruptive spirits, have been linked to witch accusations. These spirits often use the energy of a young person in a household, leading to accusations of witchcraft when bizarre events occur around them.

In Cork in 1661, Florence Newton was charged with witchcraft after an argument caused Mary Longdon to suffer fits and experience poltergeist activity. In Cornwall in 1821, a poltergeist sparked witch panic, with a mob pursuing an old woman. In 1896, a young servant girl was blamed for poltergeist activity in Edithweston. In 1983, Carole Compton was accused of being a witch in Italy due to spontaneous fires and falling objects, likely an involuntary poltergeist agent.

Witchcraft history reveals a complex mix of fear, superstition, and genuine phenomena. From ancient Rome to the 20th century, the concept of the witch has been a scapegoat for societal anxieties and unexplained events.

What’s the most surprising thing you learned about witches? Leave your comment below!