Imagine a time when a cough could be a death sentence. During the 19th century, tuberculosis, also nicknamed ‘Consumption’ or the ‘White Plague,’ was a terrifyingly common and often fatal illness. It wasn’t just a disease; it was a cultural force, weaving its way into the very fabric of Victorian life. The tell-tale signs – dramatic weight loss, a ghostly pallor, and a bloody cough – even contributed to a strangely romanticized ‘tubercular look’ that held a surprising sway over the era. Let’s explore ten fascinating ways this devastating disease left its mark on Victorian society.

High Death Rates

It’s stark but true: tuberculosis claimed an enormous number of lives in the Victorian era. In fact, it’s thought to be the deadliest microbial killer in history. As the 19th century began, an estimated 50 million people around the globe were known to be infected. What Victorians didn’t grasp for a long time was how incredibly contagious this lung-attacking disease was. The poor sanitation and hygiene common at the time created a perfect storm for TB to spread like wildfire.

Cities like London and New York were hit particularly hard. In England, tuberculosis was responsible for roughly one out of every five deaths. Similar tragic numbers were seen in the United States. As a top killer, it’s no surprise that tuberculosis touched so many aspects of daily life and society.

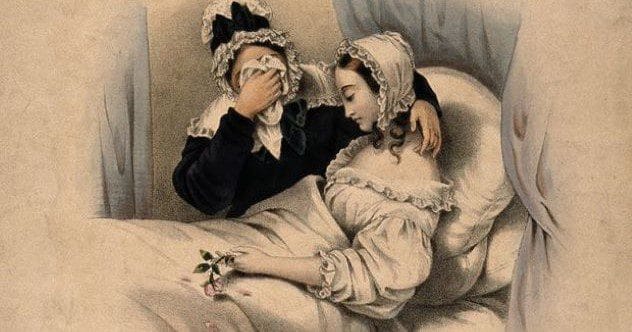

Beauty and Aesthetics

Strangely enough, at its peak in the early to mid-1800s, tuberculosis was heavily romanticized, even though it caused about a quarter of all deaths in Europe. Some of the visible symptoms, like becoming very thin and appearing to waste away, actually matched Victorian ideas of what was attractive. Because of this, TB became linked with beauty. Sufferers often had a slender, delicate build, pale skin with flushed cheeks, red lips, and bright, shiny eyes. These features were the height of fashion, leading many to try and copy this look with makeup.

Among the Victorian upper class, it was even believed that a woman’s beauty could increase her chances of getting tuberculosis. The disease was thought to enhance features already considered beautiful. Since wearing makeup was often associated with actresses or women of ill repute, many upper-class ladies actually hoped to catch the illness to achieve this desired look naturally!

The Fashion

With tuberculosis so intertwined with beauty ideals, it naturally shaped 19th-century fashion. In the first half of the 1800s, people thought ‘bad airs’ or family traits caused consumption. During this time, when the pale, wasting look was most admired, fashion trends aimed to highlight TB symptoms. Women wore tight, pointed corsets to make their waists look tiny, paired with enormous, puffy skirts to further emphasize a fragile appearance.

Later in the 19th century, when TB was understood to be a bacterial disease, it still heavily influenced fashion. Public health campaigns tried to stop its spread. Doctors warned that large skirts could drag germs from the street into homes. Corsets also came under fire for restricting blood flow and lung movement, which was thought to worsen tuberculosis. Even men’s fashion changed. The once-popular extravagant beards, sideburns, and mustaches were suddenly seen as dangerous germ-traps. Doctors and surgeons were the first to adopt a clean-shaven look, and soon, other men followed suit.

Literature

The widespread presence of tuberculosis in 19th-century Europe meant it often appeared in famous books of the era. These literary works certainly helped build the romantic image Victorians had of the disease. Tragic characters dying from TB were common, like Katerina Ivanova in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and Fantine in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables.

A peculiar belief also grew around famous writers of the time. Since so many talented individuals fell victim to TB, people started to think there was a connection between the disease and creative genius. Notable writers like Robert Louis Stevenson, John Keats, and Emily Brontë all suffered from tuberculosis. It was said their creative abilities actually sharpened as their physical health declined. Not surprisingly, this led many aspiring writers and artists to wish they could contract the disease too.

Entertainment

The idea of ‘tragic beauty’ linked with tuberculosis also made its way into 19th-century entertainment. Wealthy Victorians often attended the opera, where heartbreaking stories of beautiful tuberculosis victims were performed. Two popular operas that explored themes of the disease were La Traviata and Giacomo Puccini’s La Bohème.

La Traviata, based on a novel, is a particularly romantic portrayal of tuberculosis. It tells the story of two lovers: Violetta, a young and beautiful courtesan, and Alfredo, her secret admirer. The opera’s themes of love, youth, and beauty are shadowed by the constant threat of disease and death, with Violetta’s consumption becoming more central as the story unfolds. Given how often TB was shown in romantic contexts in the arts, it’s easy to see why Victorians came to view it as a somewhat romantic illness.

Art

Just like in literature, the imagery in many artworks by 19th-century artists was shaped by their personal experiences with tuberculosis. Artist Ferdinand Hodler’s work, for example, reflects his tragic childhood encounters with the disease, which took his entire family. Some of his most important pieces in this regard include “The Convalescent,” “Night Hodler,” and “A Troubled Soul.” It was a similar story for Edvard Munch, whose experiences inspired works like “The Sick Child” and “Sick Chamber.” Artworks like these were key in developing the more somber and tragic ideas Victorians associated with the illness.

Similar to writers, artists with tuberculosis were sometimes thought to possess a special genius. There was speculation that the low-grade fever that often came with TB might have heightened their senses, leading to bursts of inspiration and deeper insight.

An Obsession with Death

Death was a constant presence in Victorian life, and as a result, they were quite preoccupied with it. Since tuberculosis was one of society’s biggest killers (though there were several!), the disease likely played a significant role in fueling this obsession. Victorians had many rituals surrounding death and mourning, and these practices became a common part of life.

The deathbed itself became a central focus, and a person’s last words were highly treasured. In fact, “deathbed watches” and the idea of a “good death” often featured prominently in literature, especially in the works of Charles Dickens. There were complex rules for mourning; for instance, a grieving woman had to wear only black for exactly one year and a day. People made jewelry from locks of the deceased’s hair, and other mementos like death masks and portraits were proudly displayed in homes. In Victorian society, death, loss, and grief were simply accepted as an unavoidable part of living.

Science

Even though tuberculosis has been around for millennia, it wasn’t until the mid-19th century that scientists began to understand that it wasn’t just spread by “bad airs” or inherited. Around this time, French chemist Louis Pasteur and British surgeon Joseph Lister developed germ theory. While they were key in showing that germs cause disease, it was German physician Robert Koch who first linked specific bacteria to certain illnesses.

In 1882, Koch announced his groundbreaking discovery that Tubercle bacillus caused tuberculosis. His experiments, which involved growing the bacteria and then infecting animals with it, completely changed how people understood TB and similar diseases. He also found that the main way TB spread was through saliva and mucus coughed up from the lungs. This discovery led to huge shifts in scientific understanding and in the fields of medicine, hygiene, and sanitation in Victorian society.

Medicine and Hygiene

Koch’s discovery meant Victorians became keenly aware that tuberculosis was not only contagious but also closely tied to personal and public hygiene. This realization made old treatments like “a change of air” or bloodletting obsolete. Instead, public health measures were put in place to stop the spread of TB and other infectious diseases. These measures included providing clean water, removing waste properly, and creating separate sewage systems. New laws were also passed to improve housing and reduce overcrowding.

The medical field saw rapid improvements. New technology was developed to detect and treat diseases, and sterilization and antiseptic surgical procedures became standard. Specialized surgical tools and techniques also began to emerge. Ultimately, Koch’s discoveries set off a chain reaction that completely transformed the Victorian medical profession and fueled the growth of the medical industry.

Social Reform

With a growing understanding of how important hygiene and good sanitation were in preventing tuberculosis, it quickly became clear that the poorer classes were most at risk. While concerns about the living and working conditions of the poor weren’t new, Koch’s discovery certainly highlighted the urgency of the issue. As a result, fifty new housing laws were enacted in the second half of the 19th century. The main goal was to reduce overcrowding and improve the overall living standards for the poorest people in society.

Various measures, reforms, and laws were also introduced or updated to help the working class. Penny savings banks were set up, early forms of insurance policies were offered, and community resources were made available to support the most vulnerable members of Victorian society. Their susceptibility to tuberculosis and other diseases had underscored a growing need to improve their quality of life.

Tuberculosis cast a long, dark shadow over the Victorian era, influencing everything from daily life to grand societal changes. Its impact was profound, shaping perceptions of beauty, driving scientific discovery, and inspiring artistic expression. Though a tragic chapter, understanding TB’s role helps us see the Victorian world, and its challenges, with clearer eyes.

What aspect of tuberculosis’s influence on Victorian society do you find most surprising? Share your thoughts in the comments below!