Have you ever started a project with the best intentions, only to see it spiral into something completely unexpected? That’s pretty much the story of the French Revolution. What began in the late 1700s with calls for liberty, equality, and brotherhood, rooted in bright Enlightenment ideas, soon tumbled into chaos. It didn’t just change France; it reshaped Europe and the Western world in ways no one saw coming.

The 1789 revolution was just the first of several in France, making it tough to judge on its own. But one thing is clear: many events that followed strayed far from the original hopeful principles. From social breakdown to a new emperor, let’s explore 10 unintended consequences of this historic upheaval.

10. From Hunger Pangs to War Drums

Before the revolution, life in France was tough. Years of bad money management by the government created a huge economic mess. Add to that repeated bad harvests and a growing population, and many people, especially the poor, were starving and angry. Much of French society, including farming methods, felt stuck in the Middle Ages.

These were the sparks that lit the revolutionary fire. But it quickly grew into a massive historical drama. Soon after the first changes, extreme groups took charge and pushed France into conflict. By 1792, France declared war on Austria, where Queen Marie Antoinette was from. For ordinary French citizens, who went from having no bread to facing constant war, this was hardly the improvement they’d hoped for.

9. Chaos Reigns: Widespread Looting and Disorder

Instead of calming things down, the revolution often led to a breakdown of law and order. Every small step toward real change was met with more frustration. France’s problems were too deep to be solved by simply changing from an absolute king to a constitutional one. Patience wore thin. Riots, looting, and a general sense of danger became common.

Honestly, the early stages of the revolution brought moderate changes compared to what came later. The leaders at this time wanted orderly progress and respect for the law. But actions like getting rid of noble titles didn’t magically feed the hungry. With the king’s power gone, the masses, promised change but seeing little, turned against all authority.

8. A New Elite: The Rise of the Rich Aristocracy

Even though Enlightenment ideas influenced them, the revolutionary leaders were only willing to go so far. Letting everyone vote? That was off the table. Basically, to have any say, you had to be a man who owned property and paid taxes. This meant only a few million men could vote, out of a population nearing 30 million.

These property-owning men elected representatives who also paid taxes. These representatives then chose the actual officeholders. This system meant men with money picked men with even more money to put trusted allies into government. So, the old aristocracy of birth and privilege was replaced by a new one based on wealth and concentrated voting power. Unhappiness with this new setup eventually led to more extreme actions.

7. Women Sidelined: Equality Remains Elusive

Women played a crucial part in the early days of the revolution. You’d think the movement’s leaders would have been open to women’s rights. That would have matched their ideas about dismantling unfair systems. Sadly, for women, France before and after the revolution looked very much the same.

Just like the American revolutionaries, the French created a new constitution promising equality for all men. In both cases, women weren’t even mentioned. Understandably upset at being left out, political activist Olympe de Gouges wrote a women-focused version of the famous “Declaration of the Rights of Man” in 1791. Not long after, Gouges herself became another victim of the revolution’s brutality.

6. Church Under Siege: Power Stripped Away

Some early religious changes proposed by the revolutionaries were even supported by French Catholic clergy. However, these were quickly overshadowed by more extreme measures. In just a few months, the Church’s income was cut off, and its lands were taken, making it reliant on the state. In 1790, a sign of the radicalism to come was the clerical oath, requiring all clergy to swear loyalty to the new constitution.

Half of them refused, including most senior church officials, arguing their loyalty was to their faith. The Pope himself condemned the revolutionaries’ actions, which also included plans to elect clergy, thus changing the Church’s internal structure. Priests who refused to support the new constitution had to flee. These changes made religion a political issue and turned the Vatican against the revolution. The Church was officially separated from the state shortly after.

5. The Shadow of the Guillotine: The Reign of Terror

The most infamous parts of the revolution didn’t happen at the start, but after the king and queen were removed and a new republic was declared. Already imprisoned and powerless, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were executed by the republican authorities in 1793. After that, the new French Republic and its governing Committee of Public Safety targeted other supposed enemies, both at home and abroad.

Indeed, the revolutionary zeal was just beginning. Within 18 months of the king’s execution, over 20,000 people were sentenced to death or died in prison without a trial. European powers united against France, leading to a military draft, which in turn caused internal rebellions. Priests and Christianity were attacked and disrespected. Finally, in a grim twist, Robespierre, one of the Terror’s most prominent figures, was himself guillotined, becoming a scapegoat for the Committee’s excesses.

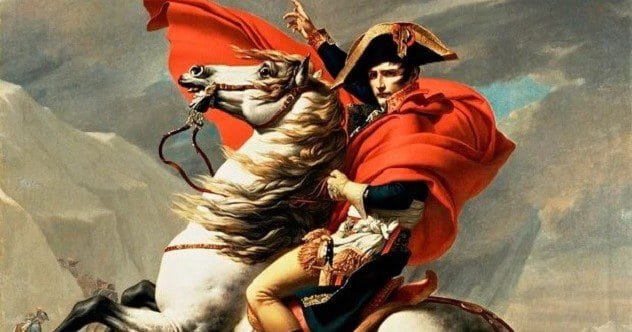

4. Trading a King for an Emperor

King Louis XVI was overthrown in 1792 and quickly executed. His wife, Marie Antoinette, met the same fate soon after, along with other royals, nobles, and anyone the revolutionary courts saw as a threat. By 1795, the king’s only surviving son, Louis Charles, reportedly died from neglect while imprisoned by the revolutionaries, though the exact details of his death remain a mystery.

Considering all the effort to get rid of the old monarchy, you’d think the French would have strongly opposed any return to similar rule. But in 1804, Napoleon Bonaparte, who began life as the son of a minor noble, crowned himself emperor after ruling as a dictator for a few years. His last reigning descendant, Napoleon III, was also, fittingly, France’s final monarch.

3. Ten-Hour Days and a Brand New Calendar

In 1792, in perhaps the strangest and most needlessly confusing move of the revolution, the first republican government introduced a new calendar. It aimed to remove the Christian and royalist influences of the Gregorian calendar. Year I of the new republic began in September. This calendar was eventually used not just in France but also in territories under French control during the revolutionary wars.

There were still 12 months, but fewer weeks since they were now 10 days long (any leftover days were treated as bonus holidays). The revolutionaries were very keen on decimalization, so each day was made 10 hours long. Imagine trying to figure this out amidst riots, political chaos, and war! Thankfully for everyone’s sanity, this bizarre experiment was eventually dropped. Napoleon abolished the calendar shortly after becoming emperor.

2. The Bourbons Return: An Unlikely Comeback

Given that the whole point of the revolution was to oust the Ancien Régime (the old ruling order), it’s safe to say the restoration of the old dynasty was its least expected outcome. But that’s exactly what happened. Just over two decades after the Bourbon monarchy fell and Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were executed, Louis’s brother took the throne as Louis XVIII in 1814, although with some new limitations on his power.

Louis XVIII’s reign was short but more successful than that of his very traditional brother, Charles, who quickly became unpopular. Charles tried to bring back some old regime characteristics, which ended badly. In 1830, another revolution swept France, but this time more peacefully. Charles agreed to step down in favor of his cousin, Louis Philippe. Louis Philippe’s own rule would end with yet another revolution in 1848.

1. The Enduring Legacy: Partisanship and Political Gridlock

It’s human to want clear endings. For those living through it, the revolution probably felt like a dramatic final act, a chapter that, once closed, would leave its troubles in the past. But the months and years that followed brought new problems, including extreme political division and a loss of faith in the democratic process.

Politically, the terms “left” and “right” are legacies of the revolution that we still use. They originally referred to where the liberal and conservative groups sat in the National Assembly. We’ve already seen the results of the breakdown in cooperation among various deputies, some mentioned in this list. Today, intense partisanship and government stalemates continue to be serious issues for nations worldwide.

The French Revolution, born from ideals of enlightenment and change, certainly reshaped the world. However, its path was filled with unexpected turns, leading to outcomes far different from what its instigators envisioned. It serves as a powerful reminder that history often writes its own surprising scripts, often with consequences that echo for centuries.

What do you find most surprising about the unintended consequences of the French Revolution? Share your thoughts in the comments below!