Audiences love stories that push the boundaries of culture, but when a work of fiction is too far ahead of its time, it can be disorienting. Without contemporary influences, these storytellers work in uncharted territory.

This can lead to unusual subversions of genre tropes, as these conventions haven’t yet been established. Even if an author correctly envisions future technology or societal norms, readers might focus on what the author gets wrong. Yet, these imaginative acts deserve appreciation.

“The Machine Stops”

E.M. Forster’s short story presents a paradox: visionary yet reactionary. It depicts people living in isolated underground rooms, communicating remotely through microphones and moving images. They rarely leave their rooms, becoming pale and flabby, cared for by a mechanical system called The Machine. A rebel, Kuno, seeks humans on the surface and wishes to escape the machine’s constraints. The title hints at the ending.

Written in response to H.G. Wells’s A Modern Utopia, it reveals a clash of influences. Wells’s Eloi from The Time Machine parallels humanity’s state within the Machine, but the Eloi’s condition results from capitalist class societies.

Written in 1909, the story remarkably prefigures synchronized sound for moving images and issues like parasocial internet relationships, and overreliance on services like Zoom. Consumer-grade radio was still over a decade away when Forster presented this vision. Hopefully, we can change our habits before it becomes too accurate.

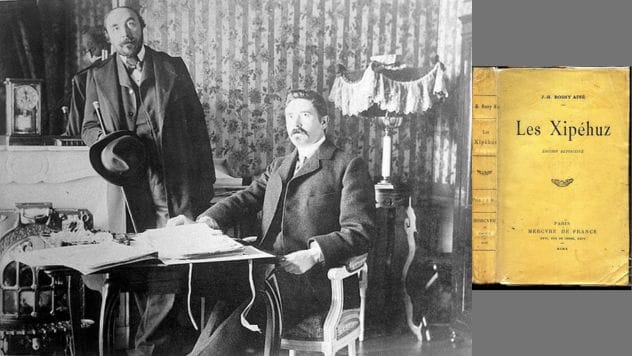

The Shapes

H.G. Wells’s 1898 novel, War of the Worlds, is often considered the first human-versus-aliens story. However, J.H. Rosny-Aine’s Les Xipéhuz (The Shapes), written in 1888, predates it. English translations were not available until Jason Colavito released one.

The Shapes tells of a Mesopotamian tribe around 5000 BC who encounter a dangerous race of blue cone, cylinder, and disc-shaped aliens, The Shapes, capable of igniting humans from afar. The humans try to sacrifice a horse, which the aliens interpret as a threat. A science-minded misfit, Bokhunen, discovers the aliens’ weakness through scientific methods.

Predating science fiction’s popularity, it goes in surprising directions. The Shapes’ origins are never confirmed to be from another planet, and death cults emerge, believing deaths are divine judgment. Bokhunen observes The Shapes reproducing by releasing spores, a scene more akin to 1970s psychedelic fiction than 19th-century historical fiction.

Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song-Book

This 1744 book is the earliest surviving printing of familiar nursery rhymes such as “Mary Mary, Quite Contrary,” “Baa Baa Black Sheep,” and “Hickory Dickory Dock.”

Strikingly, many stories would be considered unsuitable for young children today. One is literally “Piss a Bed,” and “My Mill” claims to grind “rats and mice.”

“Piss a Bed” insists that “butt” rhymes with “up.” This book reveals that the edginess in children’s entertainment existed before the Brothers Grimm in the 19th century.

The Notting Hill Mystery

Mystery fans know Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone: A Romance (1868) as the first detective novel. However, Charles Warren Adams, writing as Charles Felix, wrote the 1862 magazine serial, The Notting Hill Mystery, republished in 1865.

With no existing mystery novel paradigm, Adams made unusual choices. The murder setup, involving poison during sleepwalking and insurance policies, feels contrived. The detective, an insurance investigator, lacks emotional engagement, and the perpetrator isn’t brought to justice, diminishing catharsis. Nonetheless, the novel caused a stir but didn’t endure due to less appealing plot elements.

Romance in Marseille

Claude McKay, a Harlem Renaissance pillar, saw his novel, completed in 1933, deemed unpublishable. Published in 2020, its subject matter became fashionable: a Moroccan stowaway wins a lawsuit after frostbite leads to amputation, then mingles with prostitutes, queer characters, and socialists in Marseille.

Molly Young noted in Vulture Magazine that the only dissonant element was a stereotypical Jewish lawyer, showing even forward-looking stories carry cultural baggage.

Journey to the West

Imagine a Chinese Odyssey with a monk, colorful monsters, and comedic intent. This is Journey to the West, a Ming Dynasty novel from 1592 attributed to Wu Cheng’en, who feared its vulgar style. The novel includes scenes like the monkey king Sun Wukong urinating in the Buddha’s hand.

The breakout character, Sun Wukong, born from a rock, gains laser eye powers, frightening Heaven’s Jade Emperor. The story includes the real missionary Xuanzang (Tripitaka) and mythological beings, prefiguring crossover fiction like The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

It deconstructs fantasy tropes, such as Sun Wukong gaining immortality six times over, and has influenced works like Dragonball Z, despite being considered vulgar at the time.

“The Great Automatic Grammizator”

Before 2023, this 1953 story was not among Roald Dahl’s most famous. It involves John Knipe, who creates a machine that arranges words grammatically and develops plot structures. It generates passable stories, forcing mediocre writers to have their styles absorbed or be driven out of business.

George Orwell’s 1984 featured a “versificator” for creating government music, but Dahl’s focus on the publishing industry’s impact made it resonate seventy years later.

“The Three Apples”

While The Notting Hill Mystery (1862) was the first detective novel, Edgar Allan Poe’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841) was believed to be the first detective short story. However, 1001 Arabian Nights includes “The Three Apples,” where Jafar investigates a woman found hacked to pieces in a trunk, with a three-day deadline to avoid execution.

Jafar is passive, depending on confessions and luck, and focuses more on his fate than investigation. Societal differences make this first murder mystery stylistically different for modern readers.

“The Green Knight”

Claude McKay likely avoided commercial failure and legal trouble by not publishing Romance in Marseille earlier. However, the anonymous author of “The Green Knight” faced greater risks, as homosexuality was a capital crime when it was written around AD 1390.

Sir Gawain meets the Green Knight to trade beheadings. He stays at Lord Bertilak’s castle, agreeing to exchange trophies. Lady Bertilak kisses Gawain, who passes these kisses to the lord.

Despite changing LGBT norms, the 2021 film adaptation is less comfortable with homosexual interaction than the poem, revealing differing societal standards since the original work.

True History

This 2nd-century AD Greek tale is considered the first science fiction piece, a parody of travelogues. Lucian, a Syrian satirist, wrote guides like “Teachers of Orators,” recommending lying for success. True History begins with “I confidently pronounce for a truth, I lie.”

Lucian describes a voyage where he and his crew sail into space on a wooden ship carried by a whirlwind, landing on the Moon during a battle between moon people (riding vultures) and sun people (riding ants) for control of Venus.

They create a two-dimensional battlefield using giant spiders to weave a web between the Moon and Venus. This bizarre notion showcases Lucian’s extraordinary imagination, far removed from modern sci-fi concepts.

These stories demonstrate that imagination knows no bounds, often paving the way for future generations of creators. Each in its own way, they dared to venture beyond the conventions of their time, leaving a lasting impact on literature and culture.