Great Britain boasts a vast and impressive military history. However, sprinkled among the glorious triumphs and brilliant military minds are moments of utter failure led by shockingly incompetent generals. This list explores ten of the worst generals in British history, whose blunders led to devastating defeats and tarnished the Empire’s reputation.

1. James Abercrombie: The Disaster at Ticonderoga

While Edward Braddock is often lambasted for his failures during the Monongahela Campaign, James Abercrombie’s disastrous assault on Fort Ticonderoga in July 1758 was equally, if not more, foolish. During the French and Indian War, Abercrombie squandered thousands of lives in a pointless offensive.

The French position at Ticonderoga wasn’t invincible. The terrain offered the British opportunities to outflank the fort, and nearby hills provided ideal locations for artillery. According to Geoffrey Regan, commanders rarely face such a diverse range of options, each guaranteeing success.

Instead, Abercrombie chose a direct frontal assault, resulting in a massacre. The British lost 2,000 men, including nearly half of the renowned “Black Watch” Highland regiment, and the attack was repulsed. Edward Amherst replaced Abercrombie and captured Ticonderoga the following year with fewer troops and minimal losses.

2. Lord Raglan: The Senile Commander of the Crimean War

The Crimean War (1853-1856) epitomizes British military mismanagement. Presiding over this debacle was Lord Raglan, a former aide to the Duke of Wellington, who was completely out of his depth. Cecil Woodham-Smith noted that without his military attire, one would never identify him as a soldier.

Raglan was amiable but senile and in poor health at 65. He frequently mistook the Russians for “the French,” forgetting that France was now an ally. His inability to resolve conflicts among his subordinates, particularly cavalry commanders Lucan and Cardigan, led to the infamous Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava.

Raglan stumbled into a victory at the Alma, ordering assaults to capture and recapture the same ground, allowing the defeated Russians to escape. His mismanagement turned a potential victory at Balaclava into an unforgettable blunder, with the Light Brigade’s disastrous charge stemming from his unclear orders. His troops suffered from disease and cold in trenches before Sebastopol due to poor medical care and inadequate supplies. Raglan ultimately succumbed to dysentery in 1855.

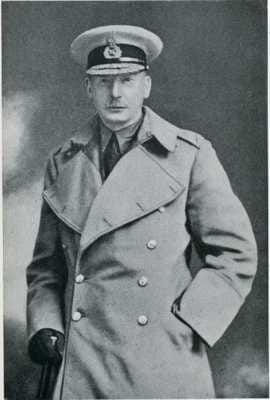

3. Redvers Buller: The Hesitant Leader of the Boer War

Byron Farwell described Buller as a “brave man who loved action but feared responsibility for the lives of others.” Buller was Britain’s equivalent of Ambrose Burnside: likeable but unfit to command an army. He repeatedly lost battles early in the Boer War, failing to grasp that infantry assaults against entrenched opponents rarely succeed. Spion Kop (January 23-24, 1900) exemplifies his incompetence.

Buller’s first mistake was delegating authority to Charles Warren, his equally inept second-in-command. Warren’s lead brigade was decimated, trapped between two Boer forces without entrenchment tools, artillery support, or effective leadership. Buller’s inaction is inexplicable, failing to reinforce Warren or capitalize on a potential flank attack. In the end, 1,500 men died needlessly, leading to Buller and Warren’s dismissal.

4. William Howe: The Revolutionary War Strategist Who Couldn’t Seal the Deal

As Britain’s commander-in-chief during the Revolutionary War, Howe won several battles and orchestrated one brilliant campaign, but nearly all were Pyrrhic victories, winning tactically but losing strategically.

Howe won the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775 but suffered 30 percent casualties. He then passively defended Boston, preferring cards to campaigning, and eventually abandoned the city without a fight.

He redeemed himself by routing George Washington’s army on Long Island and capturing New York City. However, his hesitation in attacking Brooklyn Heights allowed Washington to escape. Howe then left scattered outposts in New Jersey, enabling Washington’s easy victories at Trenton and Princeton that winter.

Howe’s final blunder occurred during the 1777 Saratoga Campaign. Instead of supporting John Burgoyne’s offensive, Howe marched on Philadelphia, winning a costly victory at Brandywine but allowing Washington to escape again. Burgoyne was defeated and forced to surrender, which brought France into the war. Howe was subsequently dismissed.

5. John Whitelocke: The Humiliation of Buenos Aires

Sir John Fortescue described Whitelocke as being “bound up indissolubly with foolish expeditions.” After spending much of his career in the West Indies, notably in the disastrous attempts to conquer Santo Domingo, Whitelocke earned his place on this list for mismanaging the 1807 Buenos Aires expedition, a costly sideshow of the Napoleonic Wars.

Whitelocke’s troops landed outside Buenos Aires on July 1st and defeated a small Spanish force. However, he delayed his follow-up, allowing local militia to organize. His troops marched into the city only to face hostile citizens, snipers, and boiling oil. Whitelocke failed to control his forces, allowing them to be divided and attacked piecemeal in the streets.

Trapped, Whitelocke surrendered to Spanish General Liniares on August 12th, having lost over 3,000 of his 10,000 men. He was dishonorably discharged upon his return to England.

6. Charles Townshend: The Siege of Kut Debacle

Driven by ambition and overconfidence, Charles Townshend led his 6th Indian Division into Britain’s greatest humiliation of World War I, losing 43,000 troops during the Siege of Kut. Ordered to advance on Baghdad in September 1915, Townshend initially expressed misgivings but leaped at the chance for glory, envisioning himself as Governor of Mesopotamia.

After initial victories, stiffening Turkish resistance and heavy casualties halted his advance. Ordered to withdraw to Basra, Townshend instead hunkered down in Kut. His men endured a horrific 147-day siege. Townshend made little effort to escape or prevent the Turks from surrounding him, even forbidding sorties because withdrawing would sap morale! A relief force lost 23,000 men trying to break the siege.

With his troops decimated by starvation and cholera, Townshend surrendered on April 29th, 1916. He enjoyed comfortable captivity in Constantinople while his troops endured forced labor. The British government censored any mention of Kut. Townshend became a Lieutenant-General, knight, and MP, but he is remembered as an arrogant fool.

7. Arthur Percival: The Fall of Singapore

When Japan entered World War II, Britain was preoccupied with Nazi Germany. The Japanese swiftly overran Hong Kong, Malay, and Burma. Singapore, the heavily fortified port known as “the Gibraltar of the East,” was the biggest prize. Unfortunately for Britain, Arthur Percival was in command.

Percival appeared to be in a strong position. His 85,000 Commonwealth troops outnumbered Yamashita’s 36,000 Japanese soldiers. However, his men were overstretched, lacking tanks or modern planes. Percival’s focus on naval attack – believing landward defenses would be “bad for the morale of troops and civilians” – ceded the initiative to Yamashita, who navigated the “impassable” Malay jungle and overwhelmed the British. Percival surrendered in what Winston Churchill called “the worst disaster in British history.”

Unlike Townshend, Percival endured harsh imprisonment. However, he became the only Lieutenant-General in British history not to receive a knighthood.

8. Charles MacCarthy: The Macaroni Massacre

What’s worse than surrendering an entire army? Utterly destroying one. James M. Perry described MacCarthy as “a decent, proud, but stupid man.” As Governor of Africa’s Gold Coast, he inherited a difficult situation and ongoing disputes with the Ashanti tribe led to war in 1824. MacCarthy mismanaged the campaign to near comic effect.

Echoing colonial mistakes made by Custer, Chelmsford, and Baratieri, MacCarthy divided his 6,000-man force into four uneven columns. MacCarthy’s own force numbered a mere 500 against 10,000 Ashanti. When the Ashanti initiated battle on January 20th, the other columns were miles away.

At the battle’s onset, MacCarthy ordered his musicians to play God Save the King, hoping to scare the Ashanti away. It didn’t work. A ferocious battle ensued and MacCarthy’s troops held their own until ammunition began running out. He called up his reserve ammunition, only to find macaroni instead of bullets!

The Ashanti massacred the British force, with only 20 survivors. MacCarthy was killed, his heart eaten, and his head used as a fetish for years. It took 50 years of intermittent warfare to subdue the Ashanti.

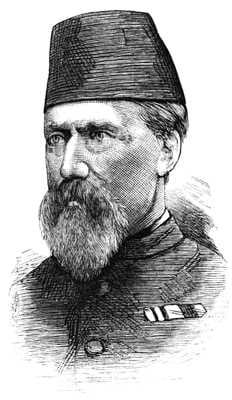

9. William Hicks: The Disaster in Sudan

Assigned to suppress the Mahdist Uprising in the Sudan, Hicks led what Winston Churchill called “the worst Army that has ever marched to war” – a rabble of Egyptian prisoners and ex-rebels, some shipped to the front in shackles. Arrogant British officials assumed this paltry force would easily subdue the Mahdists. Hicks proved them wrong.

In fall 1883, Hicks marched his army into Sudan. Misled by treacherous guides, Hicks’ army fell victim to the desert climate, losing hundreds to desertion and dehydration. On November 3rd, the Mahdists, 40,000 strong, attacked at the oasis of El Obeid. After two days of desperate fighting, the army was overrun and massacred, with all but 500 men killed, including Hicks. Hicks’ failure set the stage for Charles Gordon’s doomed stand at Khartoum.

10. William Elphinstone: The Retreat from Kabul

Britain initially won the Anglo-Afghan War, routing Dost Mohammed and capturing Kabul. However, the Afghans resented English rule and quickly revolted. William Elphinstone, the only man to lose an entire British army, stepped into this turmoil.

Afflicted with gout and heart disease, Elphinstone was a poor choice to command. He arrived in Kabul in 1842, with disaster looming. British encampments were situated lower than Kabul’s city walls, and provisions were located outside them. Afghan bandits murdered Britons who ventured out of camp.

Patrick Macrory described Elphinstone as “[seeking] every man’s advice… he was at the mercy of the last speaker.” Fatally indecisive, he allowed Afghans to kill envoys Alexander Burns and William Macnaghten, capture his supplies, and snipe at his men without response. Elphinstone finally capitulated, agreeing to withdraw his army to India.

Accompanied by thousands of camp followers, Elphinstone’s army struggled through the Afghan mountains. Their numbers dwindled due to disease, cold, and constant Afghan attacks. In the Khyber passes, the Afghans massacred the survivors. Only one European, Dr. Brydon, survived out of the 16,000 who had left Kabul. Elphinstone died in Afghan captivity.

George Macdonald Fraser aptly called Elphinstone “the greatest military idiot, of our own or any day.”

Conclusion

From the ill-fated frontal assault at Ticonderoga to the devastating retreat from Kabul, these ten generals represent the nadir of British military leadership. Their incompetence, arrogance, and indecisiveness led to countless deaths and significant setbacks for the British Empire. Their stories serve as a stark reminder that even the most powerful military force can be undone by the failings of its leaders.

What do you think? Are there any other British generals who deserve to be on this list? Share your thoughts in the comments below!