The image of the ‘mad scientist’—a brilliant mind teetering on the edge of obsession, often with a shocking disregard for ethics—was cemented in popular culture by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. While Dr. Frankenstein and his creation are fictional, history is sprinkled with real-life figures whose pursuits tiptoed, and sometimes leaped, over the lines of accepted science and morality. We all know names like Nikola Tesla, but what about those whose equally audacious, or unsettling, experiments have faded into obscurity? Prepare to delve into the stories of ten such individuals whose work will make you question the very limits of scientific endeavor.

10 Robert Cornish

Dr. Robert Cornish was a child prodigy. He graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, at just 18 and had his doctorate by 22. With such a brilliant mind, he could have pursued many world-changing endeavors. Instead, Cornish became fixated on one particular, macabre idea: reanimating the dead.

During the 1930s, working as a researcher at Berkeley, he dedicated himself almost entirely to this pursuit. Cornish theorized that if a body hadn’t suffered too much organ damage, it could be brought back to life. His method involved a custom-built machine, similar to a seesaw, designed to rock the body and restart blood circulation. This process was aided by a significant dose of anticoagulants to prevent blood clotting.

Amazingly, Cornish reportedly succeeded in reanimating two dogs. These experiments garnered enough attention to be featured in a 1935 movie, in which Cornish himself made a cameo appearance. His real ambition, however, was to reanimate a human. Finding a willing (or rather, available) subject proved difficult. For years, he petitioned prisons, hoping to use recently executed inmates for his experiments. In 1948, his wish seemed close to reality. Thomas McMonigle, a child killer on death row at San Quentin, agreed to be the subject of Cornish’s reanimation attempt after his execution. The prison also seemed open to the idea.

However, a critical roadblock emerged. Cornish needed the body immediately after execution. Prison policy, unfortunately, dictated that the body had to remain in San Quentin’s custody for several hours before release. This delay made the experiment unviable, and Cornish never got to test his ‘Cornish teeter’ on a human.

9 Alexander Bogdanov

Alexander Bogdanov was another scientist driven by an extreme goal: achieving eternal youth. Unlike Cornish, Bogdanov was a multifaceted individual. He was a revolutionary figure, an influential member of the Bolsheviks, and a noted science fiction author. His political prominence even made him a rival to Lenin at one point. After stepping back from politics, Bogdanov channeled his energy into medical studies, particularly blood research.

His influence led to the establishment of the Institute of Blood Transfusion in 1926. Bogdanov became convinced that blood transfusions held the key to rejuvenating the human body, potentially leading to significantly extended lifespans, or even immortality. He wasn’t shy about testing his theories, using himself as his primary subject. Bogdanov underwent numerous blood transfusions and meticulously documented their supposed effects. He claimed these procedures halted his balding and improved his eyesight.

Ironically, while Bogdanov believed transfusions would grant him a longer life, they ultimately caused his demise. In 1928, he died from a hemolytic transfusion reaction. This occurred after he unknowingly transfused himself with blood from an individual suffering from malaria and tuberculosis.

8 Giles Brindley

Giles Brindley was certainly an unconventional scientist, if not entirely ‘mad’ in the classic sense. He made significant contributions to the field of erectile dysfunction, being one of the pioneering doctors to show that medications could induce erections. However, it’s not his research but his method of presentation that etched him into medical lore.

The memorable event took place at the Urodynamics Society Meeting in Las Vegas in 1983. Dr. Brindley was presenting his successful findings on treating erectile dysfunction with papaverine injections. This was a groundbreaking moment, marking the first description of an effective medical treatment for the condition. But Brindley chose a uniquely vivid way to demonstrate his work. The 57-year-old doctor decided to provide a live demonstration of the treatment’s efficacy.

During his lecture, after showing slides of his own erect penis (which he conceded could have been achieved through erotic stimulation), he took a more direct approach. He casually dropped his trousers and underwear, revealing his pharmacologically induced erection to the astonished audience. He had injected himself with papaverine before the lecture to prove the drug worked without any erotic stimulus (unless, of course, he found medical symposia particularly arousing). Not content with just showing, Brindley then walked down from the podium, wiggling his erection for those in the front row, ensuring his point was thoroughly made.

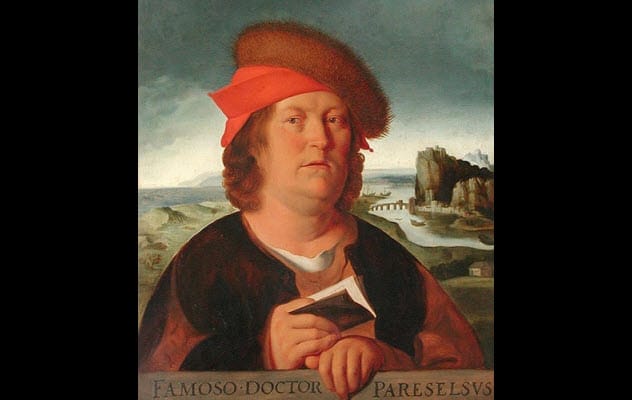

7 Paracelsus

Paracelsus, a Swiss-German physician and alchemist from the 16th century, was a transformative figure in medicine, biology, and chemistry. He is often hailed as the founder of toxicology. His key insight was that toxic substances, in small, controlled doses, could have beneficial effects. His famous dictum, “solely the dose determines that a thing is not a poison,” challenged the prevailing medical wisdom of his time, as did his use of inorganic substances for therapy.

While Paracelsus was undoubtedly ahead of his era in many respects, he also delved into alchemy and the occult. In 1537, a few years before his death, he penned De Rerum Naturae. In this treatise, he shared some of his alchemical secrets, including a particularly curious recipe: how to create a homunculus, a miniature, artificially created human.

His peculiar recipe began with human sperm, which was to be left to putrefy inside ‘venter equinus’ (horse manure) for about 40 days. According to Paracelsus, this process would result in the sperm coming to life, taking the form of a tiny, transparent human figure without a physical body. The next step was to ‘feed’ this developing homunculus human blood daily, all while keeping it in the horse manure, for a period of 40 weeks. After this, he claimed, the homunculus would be complete.

6 Wendell Johnson

Wendell Johnson, a psychologist at the University of Iowa, gained notoriety for a controversial experiment conducted in 1939. This study would later be chillingly dubbed the “monster study.” Johnson, who himself had a stutter, was a speech therapy researcher. He theorized that stuttering was not an innate condition but a learned behavior, often instilled by negative experiences during childhood. Consequently, he believed it could also be ‘unlearned’ with the right approach.

To test this, Johnson and his graduate student Mary Tudor designed an experiment involving 22 orphaned children. They divided the children into two groups. Each group contained a mix of children who stuttered and those who spoke fluently. One group received positive speech therapy. Stutterers in this group were told their speech was fine, aiming to boost their confidence and see if their speech improved. Fluent speakers received similar encouragement, serving as a control.

The other group, unfortunately, endured six months of negative reinforcement. They were constantly belittled and criticized for any speech imperfection. The most unsettling part involved six fluent speakers in this negative group. The experiment aimed to see if these negative techniques could induce stuttering in normally speaking children. Tragically, it appeared they could. Most of these children developed lifelong speech impediments as a result of the psychological pressure.

When Johnson’s colleagues learned of the experiment’s nature and its effects, they quietly suppressed the findings. However, the truth eventually came to light in 2001. Subsequently, six of the former test subjects successfully sued the university for the psychological trauma they endured, receiving a settlement of nearly $1 million.

5 Robert Knox

In the early 19th century, Dr. Robert Knox was a highly respected physician and anatomist in Britain. He was a pioneer in comparative anatomy and lectured at the largest anatomical school in the country, often drawing crowds of up to 500 students for his talks. However, Knox faced a persistent problem common to anatomists of his time: a severe shortage of legally obtainable cadavers for dissection and study.

This scarcity led Knox down a dark path that would forever stain his reputation. He became associated with William Burke and William Hare, two infamous figures who supplied him with a steady stream of fresh corpses. Their method was chillingly direct: they murdered people to sell their bodies. During their 1828 killing spree, Burke and Hare murdered at least 16 individuals, all of whose bodies ended up on Knox’s dissection table.

Although Burke and Hare were eventually caught and brought to justice, Knox was officially cleared of any direct complicity in the murders. At the time, a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ attitude towards the source of cadavers was somewhat common in medical circles. However, critics argued that an experienced surgeon like Knox should have been able to distinguish bodies obtained through grave robbing from those showing signs of violent death. The sheer number of corpses provided by Burke and Hare in such a short period—10 months—was also highly suspicious.

Regardless of his actual level of awareness, Knox’s reputation suffered immensely. Public opinion held him culpable for at least turning a blind eye to the murders. The scandal, however, did have a positive outcome: the intense media coverage and public outcry led to the passage of the Anatomy Act of 1832, which regulated the supply of bodies for medical science.

4 Andrew Ure

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a new scientific fascination gripped Europe: galvanism. Luigi Galvani had demonstrated that electrical currents could stimulate muscle movement in animals, even deceased ones. He famously made the legs of dead frogs twitch, but the public and some scientists craved more dramatic demonstrations.

It wasn’t long before these experiments extended to human cadavers. Giovanni Aldini, Galvani’s nephew, gained fame by applying electrical shocks to the body of executed murderer George Foster, causing its limbs to move. However, Scottish doctor Andrew Ure took these galvanization experiments to a shocking extreme. Like Aldini, Ure acquired the body of an executed criminal, Matthew Clydesdale. But Ure harbored a more ambitious belief: that galvanism could actually restore life to the corpse.

In a public demonstration, Ure inserted rods into various parts of Clydesdale’s body and applied electrical currents. The corpse began to convulse violently. By stimulating the supraorbital nerve, he made the cadaver’s face contort into a series of horrifying expressions. The spectacle was so intense that many witnesses reportedly fled in terror or fainted. Despite the dramatic effects, Ure did not succeed in bringing Clydesdale back to life. He attributed his failure primarily to the fact that the body had been drained of blood before the experiment, which he believed prevented the heart from regaining a pulse.

3 Carney Landis

Carney Landis might be considered a ‘mad scientist in training’ at the time of his most notorious experiment. In 1924, while still a psychology student at the University of Minnesota, he conducted a bizarre study on his fellow students and others. Landis was investigating the idea that all humans share universal facial expressions to convey specific emotions like anger, fear, or happiness.

To test his hypothesis, he recruited volunteers. He painted lines on their faces with burnt cork to better track their muscle movements when they reacted to various stimuli. Landis aimed for strong emotional responses. His subjects were made to smell ammonia, look at pornographic images, and put their hands into buckets containing slimy frogs, all while he photographed their expressions.

The experiment culminated in a particularly unsettling task: each subject was instructed to decapitate a live rat. While many were hesitant, about two-thirds of the participants eventually complied. For those who refused, Landis performed the decapitation himself in front of them. Disturbingly, one of the participants in this ethically questionable experiment was a 13-year-old boy who happened to be in the psychology department and was somehow recruited by Landis.

Ultimately, Landis’s theory about universal facial expressions proved incorrect. However, his experiment, with its focus on obedience to authority in performing unpleasant acts, unknowingly prefigured elements of Stanley Milgram’s famous obedience experiments, which would take place decades later. Landis, however, never quite realized the more profound implications his study might have had in that direction.

2 Lytle Adams

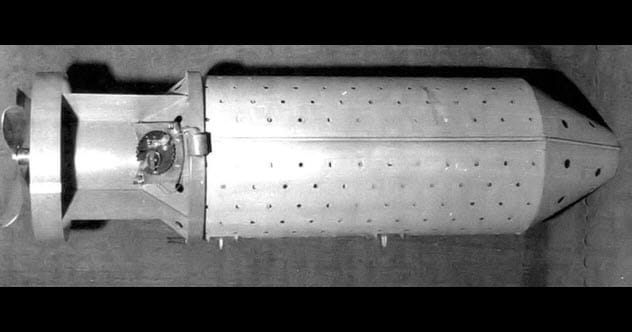

Warfare often spurs remarkable, and sometimes bizarre, ingenuity. During World War II, the United States explored a particularly unusual weapon concept known as “Project X-Ray.” The idea was to create bat bombs: bombs filled with hibernating bats, each carrying a tiny incendiary device.

The plan was to drop these bat-laden bombshells over Japanese cities. As the shell descended and opened, the bats were expected to awaken, disperse, and roost in the eaves and attics of buildings. The incendiary devices would then detonate, causing widespread fires. The project was passed through various military divisions, but after significant development and some unfortunate accidents (including one where armed bats set fire to an army airbase), it was eventually scrapped. The bat bombs were never deployed in combat.

This peculiar idea was the brainchild of Dr. Lytle Adams, a dental surgeon from Pennsylvania. He conceived of the bat bomb while on holiday, visiting the Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico. Witnessing millions of bats emerging from the cave at dusk, he imagined the destructive potential if these creatures could be weaponized to carry explosives into enemy cities. Normally, such a wild proposal might have been dismissed. However, Adams had a personal connection to Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Lady. This connection helped his idea receive serious consideration from the National Research Defense Committee. They concluded that bat bombs could indeed be feasible. An official presidential memorandum was even issued concerning Adams, stating: “This man is not a nut.”

1 Johann Conrad Dippel

Several historical figures have been suggested as possible inspirations for Mary Shelley’s iconic character, Victor Frankenstein. Andrew Ure and Giovanni Aldini, with their electrical experiments on corpses, are common candidates. However, Johann Conrad Dippel offers perhaps the most resonant connection, not least because he was actually born at Castle Frankenstein in Germany.

Dippel was a 17th-century theologian, physician, and alchemist. His relationship with religion was complex; he often shifted his beliefs to fit his circumstances. His controversial theological views frequently put him at odds with authorities and even led to him defending himself against angry mobs, further aligning his persona with the tormented, misunderstood scientist trope.

True to the ‘mad scientist’ archetype, Dippel was deeply involved in alchemy. He was active during a period when iatrochemistry—the application of chemical principles to medicine—was gaining traction. Alchemists like Dippel were keenly searching for the elixir of life, or panacea. His alchemical endeavors led to the creation of “Dippel’s Oil,” a dark, foul-smelling liquid produced by the destructive distillation of animal bones and other animal matter. Dippel claimed this concoction could treat a wide range of ailments, from epilepsy to the common cold, and even act as an animal repellent.

Dippel’s secretive work and the noxious odors often emanating from his laboratory at Castle Frankenstein fueled numerous rumors among the local populace. Many believed he was conducting gruesome experiments on human cadavers, perhaps attempting to transfer souls or even reanimate the dead. While concrete proof of such activities is lacking, his reputation, birthplace, and alchemical pursuits make him a compelling real-life figure who echoes the fictional Victor Frankenstein. The tantalizing question remains whether Mary Shelley herself had ever heard of this controversial figure born in the castle bearing that famous name.

The line between genius and madness can often appear blurred, especially when looking back at these ambitious and sometimes ethically questionable scientific pursuits. These individuals, driven by curiosity, ambition, or perhaps a touch of obsession, certainly pushed the boundaries of what was known and accepted in their times.

What do you think of these largely forgotten figures? Do any of their stories particularly shock or fascinate you? Leave your comment below and share your thoughts!