When we think of democracy, the ancient Athenians often come to mind as pioneers. Their system, however, was a world away from what we know today. It was filled with practices so unusual they might make you raise an eyebrow. Let’s dive into some of the strangest ways things were done in the very first democracy – a system that’s fascinatingly different and perhaps worth a second look.

10. Leaders Were Chosen By Lottery, Not Votes

The government of Athens was guided by a council of 500 men known as the Boule. This group was vital, managing daily government tasks and deciding which issues would be voted on. They played a huge part in leading the city-state.

But here’s the twist: Athenians didn’t vote for their council members. Instead, they used a lottery system. Fifty men were chosen at random from each of Athens’ ten tribes, simply by drawing lots. Even the head of the Boule, who managed state money, documents, and the official seal, was picked randomly! The Greeks believed voting led to power-hungry individuals taking charge. Their lottery system meant even people uninterested in politics, like Socrates, could find themselves on the council, a role he saw as a minor part of his life.

9. Every Eligible Citizen Could Vote on Every Issue

The Boule didn’t make the final decisions; every citizen did. Approximately every ten days, all eligible Athenian men were invited to a large, theater-like arena near the Acropolis. There, they voted on everything – from festival details to foreign policy and decisions about war.

Anyone present could speak. The assembly would ask, “Who wishes to address the assembly?” and any citizen could share their thoughts. However, this didn’t mean all opinions were equally respected. If a baker tried to give advice on shipbuilding, he’d likely be laughed at until he sat down or was removed. Interestingly, even though everyone was invited, turnout was often low. Out of 40,000 eligible voters, it was rare for more than 6,000 to attend. The meeting place initially only held 5,000 people.

8. Only 10–20 Percent of People Could Actually Vote

The term “citizen” in Athens was quite exclusive. In a city of about 260,000 people, around 150,000 were slaves and 10,000 were foreign-born residents, none of whom had voting rights. Of the remaining 100,000, only men aged 18 and older could vote. This meant that only about 40,000 people out of a quarter of a million had a say in how Athens was run.

There’s some evidence that, in very rare situations, some foreigners and slaves might have been allowed to vote, but details are scarce. Most often, decisions were made by these 40,000 free men – or, more accurately, by the few thousand who actually showed up. On average, only about 3,000 citizens would bother to attend and make their voices heard.

7. People Were Herded to Assemblies to Make Them Vote

Voting wasn’t always a voluntary activity. As time passed, citizens grew less interested in voting on every single decision, and attendance dropped. The Athenian authorities didn’t just accept this. They took action to ensure participation.

First, they tried paying people to attend assembly sessions. When that didn’t work well enough, they resorted to force. All markets would be closed, and roads leading away from the assembly area would be blocked. Then, a group of public slaves would carry a rope soaked in red ocher (a type of paint) and slowly walk towards the citizens, essentially herding them towards the assembly. Anyone who didn’t move quickly enough and got red paint on their clothes was fined for neglecting their civic duty.

6. Courts Had Juries of 500 People

If you think jury duty today is a bit much with 12 people, imagine ancient Athens! When a case went to court, they called in a jury of 500 peers. This meant that every time a jury was assembled, an eligible voter had a pretty good chance of being summoned.

And they used juries frequently. Minor offenses might be handled by officials, but any crime that could result in a penalty more severe than a 50 drakhmai fine (a unit of currency) required a full jury trial. These massive juries made major decisions. Political cases often came before these courts of public opinion, and the careers of important figures could rise or fall based on their verdicts. Even the famous philosopher Socrates met his end after being condemned by a jury of 500 fellow Athenians.

5. Only the Wealthiest Citizens Paid Taxes

The ancient Greeks had a different take on taxes. They didn’t believe regular citizens should be required to pay them. Under normal circumstances, the average person in Athens paid no direct taxes to the state. Instead, the government funded itself through customs duties, taxes on foreign residents, and contributions from the wealthy.

Only the very richest people in Athens were obligated to pay. Initially, this system relied on the top 1,200 wealthiest individuals, but over time, this number was reduced to just 300. Surprisingly, the wealthy often volunteered to pay even more than required. In ancient Greece, paying taxes was a status symbol, so rich men would offer extra money for military or cultural projects just to show off their immense wealth.

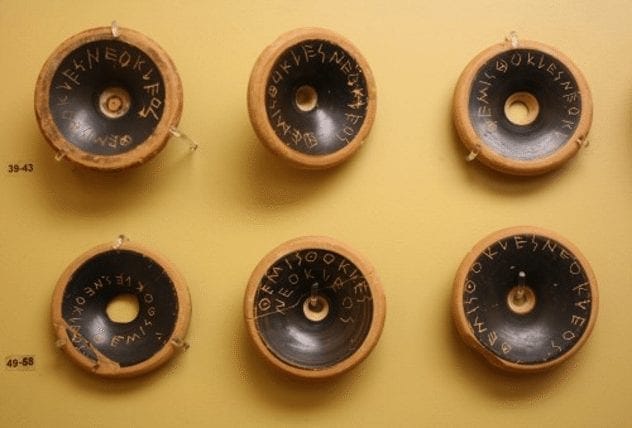

4. Citizens Could Vote to Exile Anyone for 10 Years

Once a year, Athenian citizens gathered for a unique event: the chance to banish one person from the city. They would first vote on whether to hold an ostracism that year. If the vote was yes, someone was definitely leaving.

Each citizen would receive a piece of pottery (an ostrakon) and write the name of the person they believed should be exiled. The votes were then counted. If at least 6,000 votes were cast in total, the individual who received the most votes was exiled from Athens for ten years. The main purpose of ostracism was to prevent anyone from becoming too powerful. However, people could technically be nominated for any reason. You could vote to exile your neighbor just because you didn’t like them – and some did! One man reportedly voted to exile Aristides because he found the nickname “Aristides the Just” a bit too grand.

3. Anyone Could Be Banned from Politics Through Scrutiny

Before anyone could take public office in Athens, they faced a thorough examination called dokimasia, testing their fitness for the role. Every aspect of their life was scrutinized. They could be disqualified for various reasons, from being in debt to having wasted their inheritance.

Even their family life was on trial. Officials would ask if they maintained shrines to Zeus at home, how they treated their parents, where their family tombs were located, and how often they visited them. If you disliked someone, you could force them to undergo this intense scrutiny at any time. You’d have to stand as their accuser, but you had the power to make the state investigate any citizen. If they failed the scrutiny, they would lose their right to vote and participate in politics.

2. Despite Its Ideals, It Was Still Corrupt

While some aspects of Athenian democracy might sound ideal, it wasn’t a perfect system. Just like governments today, it suffered from corruption and flaws. Although the Boule was supposed to be chosen randomly, historical records suggest that a disproportionately large number of wealthy and influential people ended up in power.

These wealthy individuals also heavily influenced decision-making. The Greeks aimed for widespread literacy, but they didn’t fully succeed; only about five to ten percent of the population could read or write. Most citizens were poorly informed and easily swayed by skilled public speakers. It was said that a small group of around 100 men could often persuade the other 40,000 voters. Even the ostracism process seems to have been tampered with. Archaeologists have found a stack of ostraka all bearing the name “Themistocles,” written in the exact same handwriting, suggesting an attempt to rig the vote.

1. Spartans Decided Things by Shouting the Loudest

Of course, Athens was just one city-state in ancient Greece. Over in Sparta, they had their own way of making decisions – and it was very Spartan indeed. They often chose leaders based on who could generate the loudest shouts of approval.

Sparta was governed by a group called the Ephorate, elected for one-year terms. While technically below the kings, some historians consider the Ephors the “real rulers of Sparta.” When it was time to choose these leaders, they didn’t use ballots. A candidate’s name would be announced, the people would shout, and the person who received the loudest cheers won. The Athenians, like the philosopher Aristotle, weren’t impressed, dismissing Spartan elections as “childish.” Yet, perhaps this loud and straightforward version of participatory decision-making, in its own way, also left its mark.

The democracy of ancient Athens was a groundbreaking experiment, but it was far from simple or similar to our modern systems. Its unique, sometimes strange, methods offer a fascinating glimpse into a different approach to governance.

What do you find most surprising about Athenian democracy? Did any of these practices make you rethink how governments can work? Leave your comment below and share your thoughts!